Partner Content: In early April the US Treasury yield curve briefly inverted, a traditional sign of an impending economic downturn. Aegon Asset Management’s Nick Edwardson discusses whether it will be different this time.

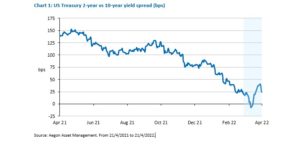

As the chart below shows, the US Treasury yield curve, as evidenced by the spread between US Treasury two-year and ten-year notes (known as the 2s10s curve), became negative for a few days in early April.

Every recession over the past 70 years or so has followed an inversion in the yield curve, albeit usually only after persistent inversions across several months. Furthermore, the average time span from inversion to recession is between one to two years. Nonetheless, this has worried commentators.

Yield curve theory teaches us that – under normal circumstances – investors require additional yield as compensation for the greater uncertainty of lending over longer time frames. Furthermore, an upward sloping (or normal) yield curve supposes that positive economic growth is expected over time, accompanied by inflation that erodes the value of money – which again requires a higher interest rate in compensation.

Yield curve theory teaches us that – under normal circumstances – investors require additional yield as compensation for the greater uncertainty of lending over longer time frames. Furthermore, an upward sloping (or normal) yield curve supposes that positive economic growth is expected over time, accompanied by inflation that erodes the value of money – which again requires a higher interest rate in compensation.

A yield curve that is flattening or inverted can signal the opposite, that investors expect or are experiencing rate hikes, but are concerned about an economy’s growth outlook. In these scenarios, yields on longer-dated debt move lower as investors expect interest rates to be cut, so seek “safe-haven” assets.

Room151’s Monthly Online Treasury Briefing

April 29 2022

Online

Public sector delegates – register here

We are sympathetic to the view that the latest 2s10s curve inversion is not necessarily a harbinger of impending doom. The argument that “this time it really is different” owes much to the unique circumstances induced by Covid 19. Furthermore, monetary policy remains very loose and elevated inflation due to supply-chain disruptions and commodity scarcity has been amplified by the Russian/Ukrainian war. But the scale and persistence of this inflation is changing perceptions. The US Federal Reserve has begun hiking and markets increasingly expect a series of more hawkish hikes.

We are sympathetic to the view that the latest 2s10s curve inversion is not necessarily a harbinger of impending doom. The argument that ‘this time it really is different’ owes much to the unique circumstances induced by Covid 19.

Impact of QE

It has been argued that the unprecedented amount of quantitative easing (QE) that has been pumped into economies and markets has materially distorted longer end rates by “anchoring” them at artificially low levels. With inflation high and nominal rates low, real rates remain quite negative; hardly restrictive financing conditions to hamper economic activity. Here again, things are changing, the Fed is now expected to begin reducing its balance sheet, reversing the QE that markets have enjoyed.

If not impending recession, curve inversions do often signal a near-term cycle transition, in this case from mid- to late-cycle. Given the speed of the bounce back from March 2020, we are likely further through the cycle than markets think. Risk markets may have been remarkably stable compared with the sharp sell-off in government debt markets, but there is likely more pain to come in bond markets, at least while continued high inflation prints force central banks to step up their game.

During past periods of economic uncertainty, risk markets have been helped in no small part by a 40-year bond bull market. If we are indeed entering a new era of higher government bond yields, asset allocation decisions will be influenced by what additional risk premia is warranted in a world of structurally higher and perhaps less predictable “risk-free” assets.

There must also be a risk that “this time it really is different” in one other way. That the supply problems causing inflation do not respond to tighter policy as demand-led inflation would, that the rate rise medicine is inappropriate for the inflation fever. For now, with the recovery in corporate metrics (margins, for example), few signs of any meaningful economic distress and still quite loose monetary policy, equities remain our preferred asset class within multi-asset portfolios. But for how long? The risk that a central bank policy mistake or conflict escalation takes us closer to stagflation or recession is growing.

Nick Edwardson is senior multi-asset investment specialist at Aegon Asset Management.

—————

FREE weekly newsletters

Subscribe to Room151 Newsletters

Room151 LinkedIn Community

Join here

Monthly Online Treasury Briefing

Sign up here with a .gov.uk email address

Room151 Webinars

Visit the Room151 channel