For those with a sense of humour IFRS 9 is sadly no practical joke. It’s time to prepare for impairment losses… and a game of Jumanji.

While we wait expectantly for Easter Sunday, hoping that Sajid Javid will burst through the door scattering wads of cash from overstuffed pockets and cackling “April fool!”, remember also that 1st April is the implementation date for IFRS 9 Financial Instruments.

There has been plenty of talk about IFRS 9’s potential effect on accounting for investments, with the default treatment switching to “fair value through profit or loss” — ie, gains and losses in fair value being recognised as income and expenditure when they arise, rather than being deferred until the investment is sold or matures.

Much work has been done to identify investments that might be at risk of a changed accounting treatment which wouldn’t be protected by the option to designate a “fair value through other comprehensive income” treatment, or qualify for adjustment under existing statutory reversals.

Risk still attaches to pooled investments that aren’t based on the holding of shares in the fund or puttable money market funds (ie, those where you have an absolute contractual right to put your shares back to the issuer in return for cash).

Relegation chances

Not so much publicity has been given to the other major change coming with IFRS 9: a more pessimistic approach to impairment losses for investments and debtors. The change is designed to ensure proper provision for credit risk, rather than waiting for an investment, loan or debtor X to actually turn bad.

The current model for impairments (incurred losses) only requires balances to be written down where there is evidence at the balance sheet date that contractual amounts due will not be paid, no matter how likely it is that there might be a default in the future.

The new model (expected losses) requires provision based on expectations for the whole remaining life of the investment or debtor, taking into account the different adverse developments that could take place and the losses that would then arise, weighted for the likelihood that the developments will happen.

A rescue loan to the local football team provides a good example of the differences between the two models. If it is assessed that there is little prospect that the loan will be repaid if the team gets relegated, under the incurred losses model, no allowance for impairment would be made until survival was beyond even Sam Allardycean acts of heroic deliverance.

With expected losses, the chances of relegation at any point over the life of the loan could need to be factored in to calculations.

Crystal

The re-introduction of crystal ball gazing will mean that loss allowances will almost inevitably need to be bigger from 1 April.

There are, though, some ameliorating factors:

- Many authorities did not effectively apply the incurred losses model, either because they ignored its introduction as part of the transition to IFRS accounting or because they identified it was imprudent and topped up allowances by setting aside earmarked reserves to cover credit risk.

- Allowances are likely to be immaterial for investments with top-rated institutions or where there is effective security.

- For many balances (such as debtors for goods and services) the two models have largely the same practical effect.

- Non-contractual balances (eg, council tax and NNDR arrears) are outside the scope of the changes.

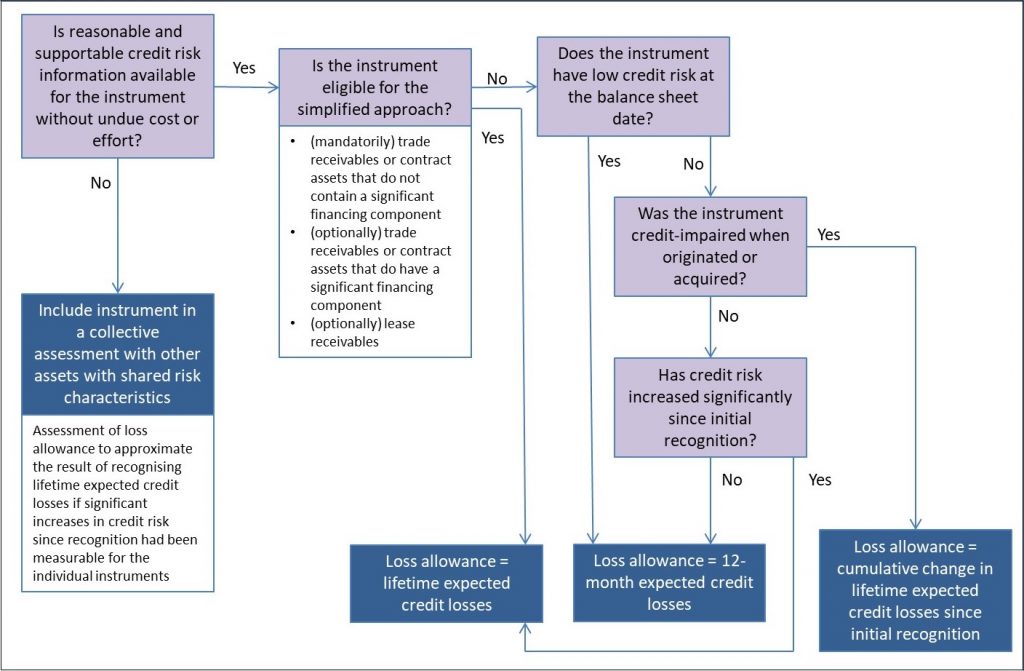

For those investments and debtors that will need reassessment, I present without further comment a flowchart to illustrate the new world with which you are about to become familiar (don’t forget to shout “Jumanji” when you make it to the end):

The greatest risk for a substantial hike in loss allowances will apply to unsecured loans with higher credit risk that has yet to crystallise and finance lease receivables.

Even though in many cases the allowance can be restricted to cover only the effects of those events that could happen in the next 12 months, a sizeable sum might need to be provided for as soon as the advance is made or the lease entered into.

Increases in loss allowances at 1st April 2018 will be posted against the general fund balance.

However, where the allowance relates to an item covered by the statutory definition of capital expenditure (eg, loans towards capital expenditure incurred by others, finance leases), the debit can be reversed out of the balance.

But even though reversible, the calculation of the allowance should be a relevant factor in the alternative capital financing arrangements made for potential future losses arising from the loan or debtor.

To a great extent, then, this element of IFRS 9 will cause you to think more deeply about credit risk, but it will not generally have a substantial impact on resources, if managed appropriately.

However, there will probably be some individual instances of material increases in allowances that will not be reversible, particularly loans to organisations and individuals with significant credit risk that are not for a capital purpose and which do not have adequate security.

It is a relatively urgent task, then, to establish whether your authority is potentially exposed to hits on the general fund balance from these changes. This is not a change in accounting rules that can happily be left to 2018/19 closedown to sort out.

Stephen Sheen is the managing director of Ichabod’s Industries, a consultancy providing technical accounting support to local government.