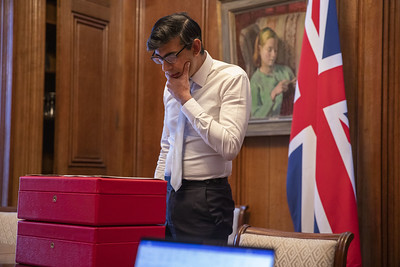

Chancellor Rishi Sunak offered local authorities a 4.5% increase in core spending power for 2021-22, the ability to raise council tax for social care and new money for Covid losses. Adrian Jenkins writes while money remains tight the deal improves than some recent years.

Every time we analyse a settlement or spending review, we are always trying to answer the question: is it a good settlement for local government? In the last couple of years, the answer is – unhelpfully – it depends how you look at it! The spending review delivered by chancellor Rishi Sunak this week is no different: on some measures, the funding allocations are reasonable, particularly in the context of the savage impact of Covid on the public finances. But local government is still very short of funding (the LGA’s fund gap will have reduced, but not by much) and the medium-term financial health of the sector remains uncertain.

Local government’s Core Spending Power (CSP) will increase by 4.5% (£2.1bn) in cash terms in 2021-22. That is not as good as 2020-21 (where the increase was 5.1%) but it will be much better than in the recent past. In the previous multi-year settlement, CSP barely matched inflation in years 2017-18 to 2019-20, and actually reduced in cash terms in 2016-17. So, it is good for local government that overall resources are increasing both more quickly than inflation and much more quickly than in the recent past.

Local government’s Core Spending Power (CSP) will increase by 4.5% (£2.1bn) in cash terms in 2021-22. That is not as good as 2020-21 (where the increase was 5.1%) but it will be much better than in the recent past.

The national picture is bleak, with the budget deficit expected to be nearly £400bn this year (19% of GDP) and net debt exceeding 100% of GDP for the foreseeable future. The impact of Covid on the public finances will be more than twice that of the Financial Crisis a decade ago.

Nevertheless, the chancellor has been keen to explain that there will be no return to “austerity”. Although not particularly well defined by the chancellor, that probably means no cash-terms cuts in funding—and indeed, no department will have cash-terms cuts in their budget in 2021-22 (although baselines are very difficult to unpick because the movement is so great because of COVID). Beyond the headlines, though, the chancellor has reduced day-to-day spending across the public sector by about £10bn.

12th Local Authority Treasurers Investment Forum & FDs’ Summit

NOW A VIRTUAL EVENT + ZOOM151 Networking

Jan 20, 21 & 22, 2021

Burden

When we look inside local government’s allocations, however, there are some troubling developments. Resources for adult social care are expected to increase by around £1bn—that is less than in the current year, but more than in the previous two years. Worryingly, though, the mix has started to shift from centrally-funded grants to locally-funded increases in council tax. Social care authorities will be able to increase their Band D council tax by 5% in 2021-22: 2% core increase, 3% adult social care precept. But the increase in grant funding for social care is the lowest since 2016-17.

A greater burden is being placed on the local taxpayer to fund the increasing cost of social care. And in local government, this matters because the ability to generate council tax income varies enormously from authority to authority.

Some authorities (typically in south-east England) will generate more per head than authorities elsewhere. Many authorities will just not use the full increase in council tax that is available to them (especially those with local elections in May) and it is likely that authorities will be able to defer some of the 3% increase into 2022-23.

A greater burden is being placed on the local taxpayer to fund the increasing cost of social care. And in local government, this matters because the ability to generate council tax income varies enormously from authority to authority.

Funding from central government for the effects of Covid in local government are more positive, even if they are not perfect. A further £1.55bn will be available to fund expenditure on the coronavirus in the first quarter of 2021-22 (we would like the allocations from this fund to be confirmed in the provisional settlement), and it has been announced that the sales, fees and charges compensation scheme will be extended into the first quarter of 2021-22 as well.

A new scheme to fund losses in council tax and business rates has been announced. The scheme will fund 75% of unrecoverable losses—which will not be finalised for years—and the Treasury has estimated this will cost £762m. Overall, these compensation schemes are good but local authorities will still be funding 25% of their income losses.

Distribution

Within the overall allocation to local government there are some distributional issues still to be resolved. Authorities with large amounts of accumulated business rate growth will breathe a sigh of relief that they will be allowed to keep all their growth for another year. Many authorities, though, are frustrated at the lack of clarity about New Homes Bonus which, for many shire districts, is crucial to their budget setting in 2021-22. Shire districts are coming out of the spending review worse than other types of authority because they have less ability to increase Band D council tax and they are more reliant on New Homes Bonus which is being phased out.

With the exception of 2020-21, the sector’s settlement next year will be better than anything for over a decade.

A decision has been deferred again on the future reform of local government funding (or even when it will happen). Levelling-up and how it will affect local government is not explained and an increasing reliance on council tax suggests its implications for local government finance are still undeveloped. The new £4bn “levelling-up fund” is bid-based and very much controlled by Whitehall.

So, how should local government judge the spending review? Overall, it is broadly in line with expectations, and it is better than we have been used to in the recent past. With the exception of 2020-21, the sector’s settlement next year will be better than anything for over a decade. A cash-terms increase in grant funding combined with the ability to increase council tax well-above inflation puts local government in a better financial position than some other parts of the public sector.

The increased reliance on council tax is concerning, though. There is a limit to how much can be generated from an unreformed council tax system where yield varies so much across the country. It is unlikely that increases in council tax combined with real-terms cuts in grants will be enough to put local government on a sustainable financial footing over medium term.

Looking further into the medium term, the scale of “fiscal consolidation” is going to be enormous (at least £27bn according to the Office for Budget Responsibility). Fortunately for local government, most commentators expect the bulk of the “consolidation” to be done through increases in taxation rather than spending cuts. In that context, local government’s allocations in the 2020 Spending Review are preferable to the large cash-terms cuts in funding of previous decade. A continuation of the type of settlements announced in the 2020 Spending Review would certainly leave local government with a chronic shortage of resources but it might be the new normal.

Adrian Jenkins leads the funding advisory service at Pixel Financial Management.

Photos (cropped): HM Treasury, Flickr.

FREE monthly newsletters

Subscribe to Room151 Newsletters

Monthly Online Treasury Briefing

Sign up here with a .gov.uk email address

Room151 Webinars

Visit the Room151 channel