Andrew Hardingham looks at the underlying issues that caused more than a third of respondents in the Room151/CCLA treasury survey to say that the funding system for local govenrment is “broken”.

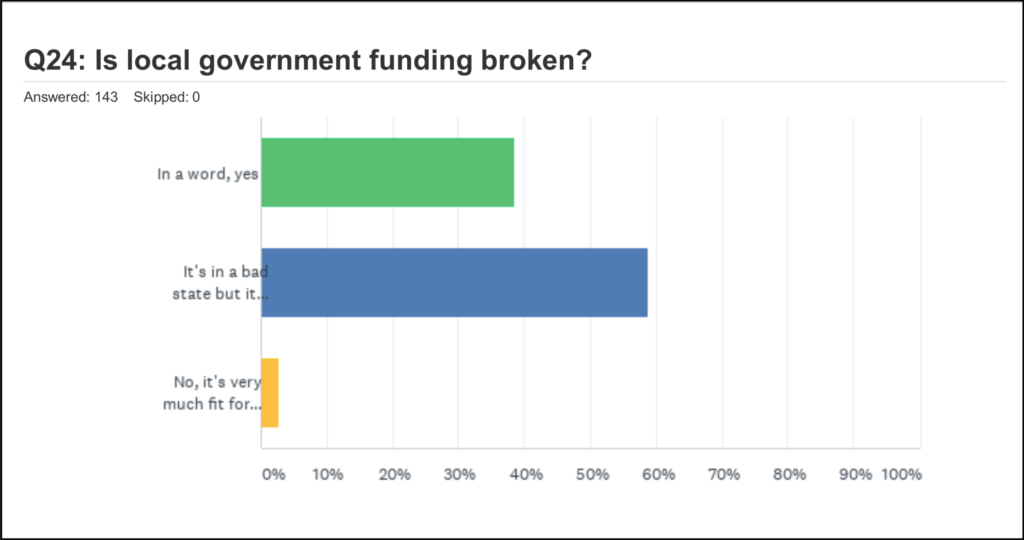

In Room151’s recent Treasury Investment and Current Affairs Survey, only 3% of 143 respondents believe that the current system for funding local government finance was fit for purpose. More than 38% believe it to be broken. The remainder sat on the fence. In danger of falling off, they believed it to be in a bad state but not broken.

Respondents were from across the local government landscape: Counties (10% of respondents), unitary and city councils (24%), districts (27%), metropolitan and London boroughs (23%). Police and fire authorities had their say too.

The fact that so many respondents believe that the cash they previously stored up and carefully invested would be eroded over the next few years (67% thought investment balances would fall) suggests that councils will be drawing heavily on reserves to supplement their resources and indicates the system is not working.

To watch a full discussion of the Room151 and CCLA treasury survey, click here.

To try to understand why so many might consider the system broken, it is important to understand exactly what is alleged to be broken.

We all know that local authorities’ resources come from council tax (a tax on property owned or rented by the electorate) and non-domestic rates (a tax on property owned or rented by business and, if you are one of the lucky ones, revenue support grant (RSG).

These core resources are supplemented by a plethora of specific grants, many with explicit terms and conditions attached, plus others top sliced from RSG pot (e.g. new home bonus).

There are so many different grants that it is difficult for CFOs to keep up and maintain a medium term financial plan with any certainty.

Resources

Let’s have a closer look at these resources. Council tax was introduced in 1993 after the political disaster of the community charge (poll tax) which forced the poorest to contribute more than they had under the old rates system.

Protests, riots and campaigns of non-payment forced the then government into a rethink that resulted in the birth of “council Tax”.

Thirty years on, it is still a tax system based on property values from April 1991. Its burden falls disproportionally on the lowest incomes. Government has made “tweaks”, the biggest being the creation of an adult social precept, a great example of central government pushing the “blame” for the tax onto local councils and the burden-to-pay for the care part of the health system onto local residents.

Council tax as a proportion of local authority income is growing whilst the ability to make local policy contracts.

With the introduction of the poll tax, the burden for rates was shifted solely to business. Currently, local government collectively retains about 50% of the income from business rates.

The other half (after a few adjustments) is paid back to councils by central government in the form of grants. There has been much debate about reform. Unfortunately, debate is only what it is.

Room151’s Monthly Online Treasury Briefing

February 26th, 2021

Sustainable investing for treasurers

Register here with a .gov.uk email address

This would tend to strengthen the belief of brokenness: It seems that no one knows how to mend it. There are so many reliefs to business that one is left to wonder whether it would indeed be kinder to put a dying system out of its misery.

A business can claim small business rate relief, rural rate relief, charitable relief, hardship relief, transitional relief, retail discount, exempted buildings and empty buildings relief. Those in enterprise zones get relief.

By the end of December 2020, my old authority received nearly half of its business rates income in the form of a Local Government Act 2003 “Section 31 grant”. The legislation quaintly states: “A Minister of the Crown may pay a grant to a local authority in England (and Wales) towards expenditure incurred or to be incurred by it … with the consent of the Treasury”, i.e. income from government not from business. Is this an indicator of a fair tax or a broken system?

Revenue Support Grant is the central government grant given to local authorities which can be used to finance revenue, supplementing council tax and rates. Between 2015 and 2020, RSG has fallen by 77p in the pound with almost half of councils no longer receiving RSG.

The new homes bonus, created in 2011, redistributed some of the grant by incentivising councils to grant planning permissions for the building of new houses in return for additional revenue. However, where the government initially matched the council tax raised on each new home built or reoccupied is now in danger of disappearing.

Largesse

These are the constituent elements of a funding system controlled by central government and bequeathed as largess to grateful CFOs who are charged with making sense of it all for elected members.

Not only is the structure of the system considered to be broken but the timing of what now appears to be an annual local government finance settlement announcement is crass.

CFO’s work all year to advise the management of service budget demands, assessing savings proposals, recalibrating service levels and resources but have to wait until December for the government’s contribution only a few working weeks before CFO’s are required to sign off budgets as robust and reserves as adequate. What could be more broken than the process?

Councils are seeking new ways to raise income: Some are investing in commercial property to create revenue streams. Is this a symptom of a broken system that forces councils into, hitherto considered by many, too risky ventures?

The LGA has argued, inter alia, for financing of local government services to be sufficient, for a system that is fair, a tax that is efficient to collect, predictable and transparent.

That reminds me, what did happen to the fair funding review? Was that to be the solution or a sticking plaster? The National Audit Office, concluded in a 2018 report “the financial future for many authorities is less certain than in 2014. The financial uncertainty created by delayed reform to the local government financial system risks longer-term value for money.”

Whilst the long awaited review is to be welcomed, it must focus on the quantum of resources not just the redistribution. Surely the fundamental outcome of the review has to be to mend the brokenness.

Andrew Hardingham is an independent adviser and a former section 151 officer at Plymouth City Council.

Photo (cropped): Andrew Parsons / No 10 Downing Street, Flickr

FREE monthly newsletters

Subscribe to Room151 Newsletters

Monthly Online Treasury Briefing

Sign up here with a .gov.uk email address

Room151 Webinars

Visit the Room151 channel