There is much finger pointing but no one prepared to take the blame for the financial troubles and effective bankruptcies at local authorities. These situations will arise again and again until the underlying problems are identified and responsibility is taken, says Conrad Hall, corporate director of resources at the London Borough of Newham

Who broke my local council? It’s a pretty topical question, isn’t it? Croydon, Slough, Thurrock and now Woking have tested to destruction the theoretically correct notion that a local authority will always be a going concern.

Before I turn to the question of whose fault it might be, I must make a confession. Levels of debt, the structure of it, commercial activity and governance arrangements have been a consistent theme in local government failure, but also, it seems to me, of Thames Water, which may be on the verge of a bankruptcy that would put all of the above combined into the shade. Am I the only person in the sector who felt a guilty sense of relief when Thames Water reminded us that, whatever a local authority can get wrong, the private sector can do it even worse and get paid bonuses to boot?

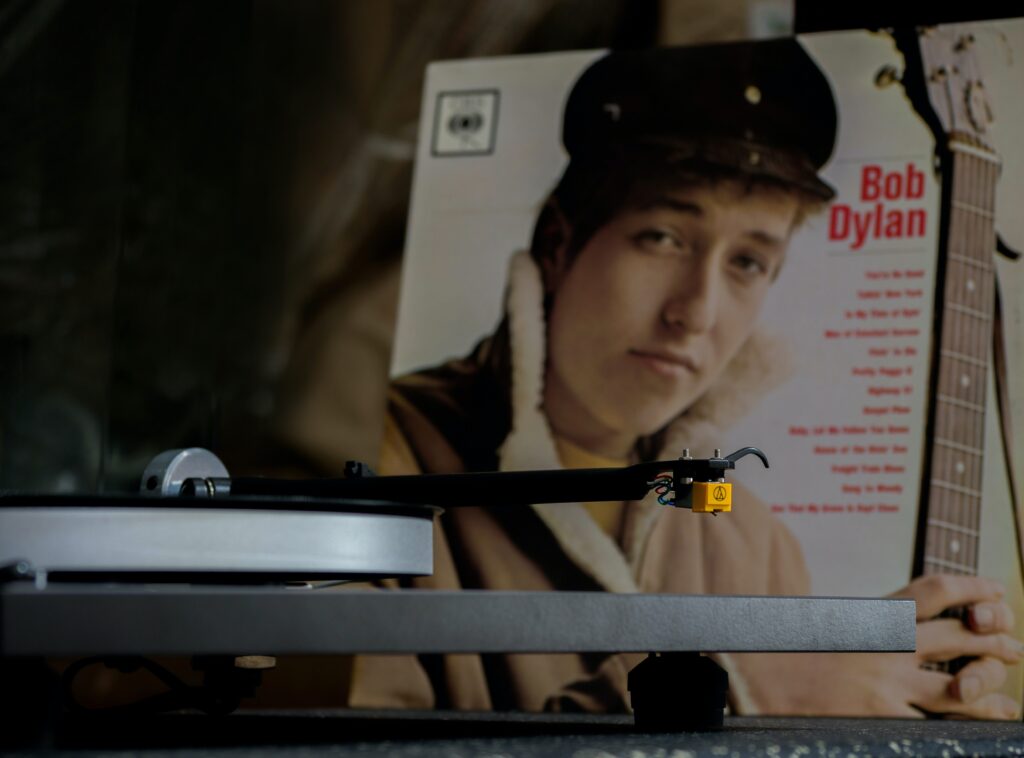

But back to local councils, debt and bankruptcy, and the story of Davey Moore might be instructive. Davey Moore was a boxer in the 1960s who died during a boxing match/legalised fight (delete according to choice). Bob Dylan took up his tale, with the plaintive refrain:

“Who killed Davey Moore

Why and what’s the reason for?”

The song draws heavily on the folk tradition, as a list of characters deny responsibility despite their obvious connections to the events. His opponent says: “I hit him, yes, it’s true; But that’s what I am paid to do”, and others similarly absolve themselves of blame, most memorably for me the gambling man: “My hands never touched him none; I didn’t commit no ugly sin; Anyway, I put money on him to win”. And yet, despite this long list, a man is dead and his grieving wife must tell his children that they no longer have a father.

Playing the blame game

So, when a local council goes bankrupt, whose fault is it?

Of course it will depend on the exact circumstances, but whereas success has many parents, failure is an orphan, and we can be sure that all the protagonists will find a justification for their own actions.

Within the local authority, the political leadership will say, with no little justification, that they relied on professional advice from highly paid officers who were supposed to know what they were doing.

Moreover, whilst the commercial investments that were probably at least a part of the cause were doing well, they were able to use the income to deliver more and better services. Who wants their politicians only to aspire to manage decline? Wasn’t chasing a commercial return a better alternative to seeing vital local services wither on the vine? And anyway, where were the Audit and Overview and Scrutiny Committees: wasn’t it their job to spot these problems early?

The finance director may be able to point to sections in the reports that authorised the transactions that spelled out the risks. However, there comes a point when, as a s151 officer, you have to call it: if the report says proceed with whatever the transaction is then that’s what you think should be done and the section on risk is just trying to limit your liability.

Finance directors may also be able to point, with considerable justification, to the pressure that they were put under by chief executives or their management teams. That said, you still have some statutory protections, although these were shamefully reduced a few years ago. It’s also vital to remember that there is a collective responsibility for these things. If directors of children’s services think it’s essential that every job description in the council includes a “safeguarding is everyone’s business” clause, then they too must be actively involved in discussion about the levels of debt-financed commercial risk that the authority takes on. Does that happen in your council?

What about the auditor? I have little sympathy with the argument that the global accountancy firms don’t have the capacity to deliver the audits that they chose to bid for at a rate that they thought would earn them an appropriate return.

But is delayed audit completion really the problem here, as some have claimed? After all, everyone now seems to agree, with hindsight, that it was absurd for Woking, on a net budget of some £20m, to hold around £1.9bn of debt. But four years ago the LGA peer review seemed pretty positive about their commercial strategy, when the ratio was not much less, at £1.2bn to £20m. It’s rather depressing that we seem only to be able to say with hindsight that this was obviously wrong: whether the auditor or someone else, aren’t we paying for foresight, not hindsight?

Maybe the audit regulators and standard setters need to take a long look at themselves. If the audit is important – and if you don’t think it is then you’ve given up on prudent public finance – then surely there is a role somewhere for them to require auditors to do more than conclude that the accounts accurately describe the dire situation. Shouldn’t the audit requirement, in a public sector context, go beyond this narrow definition and require more calling out of the issues, again with foresight not hindsight?

15th Annual LATIF & FDs’ Summit – 19 September 2023

250+ Delegates from Local Government & Investment

I think that the VFM audit is the weakest part of the whole public audit framework; I’ve certainly had no meaningful insights from it at authorities I’ve worked at for close on twenty years. Regulators, in my view, need to require a shift in audit focus, from more abstract technical valuation issues back to the fundamentals that the ordinary resident thinks they are paying for.

And let’s not forget government’s role in all of this. Back in 2010 there was a very strong steer from government that local authorities should be more self-financing, because there wouldn’t be much cash from annual settlements. So if the sector did this, and took risks accordingly, is it really a surprise that some of those risks crystallised?

Really, if you pursue this one to its logical extreme, you should surely expect some failure. With something like 350 local authorities, or whatever it is, if 1% of them get in to trouble, you could argue that they weren’t taking enough of the risks that government wanted them to. Perhaps a 5% figure would be much more commensurate with the government’s implied and explicit statement of risk appetite, and that the limited number of failures that we’ve seen to date therefore mean that the sector is actually doing pretty well.

The ballad of broken councils

One could list more protagonists, more accusations of failure and ever more vehement denials. The facts will be determined in each case, but we need a wider view across the sector of what the underlying problems are that need to be fixed. Without a changing of the guard, and quickly, Woking won’t be the last time we have this debate. I don’t know what all of the answer is, but I do know it can’t consist of everyone looking for someone else to blame.

We need a spokesperson for a generation to nail that one. Bob Dylan was widely considered to be that, even though he famously rejected that label with his brilliant line “Don’t follow leaders”. His career has spanned unimaginable heights and dreadful lows, but safe in the knowledge that even at his nadir, the angry genius who penned Masters of War and Positively Fourth Street, would never descend to trying to sing the refrain below, I offer you:

Who broke my local council?

Why and who will pay the bill?

Not I said the council leader

They told me it was all OK

Anyway, which other services should I have cut?

We had to do something to get out of the funding rut

Who broke my local council?

Why and who will pay the bill?

Not I said the management team

We had a finance director for that stuff

I didn’t understand it, yes it’s true

But I had other things to do

Who broke my local council?…

Not I said the finance director

Sitting in their spacious office

I told them all about what could go wrong

Even if it was on page two hundred and seventy one

Not I said the government

I told them to be commercial, true

But really not to this degree

And, compared to council tax, I thought it was money for free

Not I said the auditor

My job was to check the books and not advise on risk

The accounts might have been true and fair

When I got round to auditing them

Not I said the regulator

I didn’t do the actual work

I didn’t commit no actual sin

Anyway, at least the PPE was valued right

But local councils are going bankrupt, and if no one can sort out who is to blame then it will happen again and again. And someone will have to tell the citizens that they can no longer have local services.

Conrad Hall is the corporate director of resources at the London Borough of Newham and chair of the CIPFA LASAAC Local Authority Code Board

—————

FREE weekly newsletters

Subscribe to Room151 Newsletters

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us here

Monthly Online Treasury Briefing

Sign up here with a .gov.uk email address

Room151 Webinars

Visit the Room151 channel