Brexit has turned into a “shambolic” saga, according to Bob Swarup who says the investment returns born of the UK’s divorce from Brussels may be small while the risks are large.

“Uncertainty is not an indication of poor leadership; it underscores the need for leadership.”

Andy Stanley

“To think is to differ.”

Clarence Darrow

“Success comes not from having certainty, but being able to live with uncertainty.”

Jeffrey Fry

As political processes go, Brexit must truly be one of the most shambolic in recent years. In fact, it is rapidly turning into an unspeakable expletive of the bovine variety.

A combination of misguided political “astuteness”, lack of coordination and certainly no consultation has led to the unique situation where the UK is marching into a negotiation where no one actually knows what our starting position is.

While there is something to be said for holding cards close to one’s chest and maintaining a poker face, the rules of card playing still require you to know in your own mind what your hand is, what you are seeking and what you are willing to sacrifice to win.

Unfortunately, the UK as an establishment appears to have retreated from these basic tenets with conflicting messages from different members of government, often open disagreements and the complete lack of any consensus on any issue. Other than the fact we are leaving. Ish.

Are we for a soft Brexit or a hard Brexit? Are there red lines that cannot be crossed? Are there items we are open to negotiations on? Do we have a countervailing divorce number in mind, even if that number is zero? Is there a priority list of regulations to preserve, emulate and shred? What is the strategy for key sectors of the economy? Do we intend to use this process to help rebalance the UK economy? Has the government earmarked pools to compensate for lost grants, transitional arrangements, export

subsidies and the like? What is the cost of these versus the savings, and is a fiscal assessment underway? Has anyone considered the impact on and potential mitigants for cross-border transactions, supply chains, airline and train logistics, public sector resource bottlenecks etc.? Do we have even a shred of a common manifesto of aspirational policies, something that political parties otherwise seem so fond of laying out at every point?

These are not simply shades of political leaning or questions to ponder over a pint at the pub. Rather, these are important contours that set the scene for investors by giving them some inkling of the macroeconomic and investment landscape that they are trying to navigate. They represent a view of the world that we can take as a base case scenario and plan our strategies and frameworks around.

In their absence, we are unfortunately instead left grappling with uncertainty, that larger and scarier cousin of risk. The danger for financial markets and many local authorities is that faced with this, they elect to stay with the status quo in the absence of direction.

That is dangerous.

Uncertainty may not be quantifiable but it can still be analysed and the risks hiding within assessed. Doing so is critical if we are to proactively manage portfolios, safeguard them against emerging risks and eke out returns alongside.

As one example, we wrote recently about the corrosive impact of inflation on local government balance sheets and the need to manage the issue holistically.

But inflation is just one dimension of this complex landscape.

Macro

On a macroeconomic level, the Bank of England finds itself in an unwelcome place. The uncertainty of Brexit, notwithstanding the abdication of leadership, had already forced the Old Lady to pursue a more dovish line, as it looked to support the economy.

Now the election, and the hung parliament it has produced, have created a larger dilemma. The lack of a clear political mandate and consensus has meant the path forward is more uncertain than ever. The lack of clarity over what kind of Brexit the UK will want to pursue means a journey of greater volatility and greater risks to the economy.

That implies a central bank that is loath to raise interest rates in the main. At the same time, it faces two competing pressures.

First, there is the afore mentioned inflation, which is set to steadily rise as the pound weakens and with the added pressure of wage inflation as society tires of austerity. Given the explicit mandate of managing to an inflation target of 2% and the dangers to growth, the Bank of England will be all too aware of the risks building here.

Second, there is the need to rein in a runaway credit expansion and build up the capacity to fight the next crisis. We are now a decade on since the last crisis began and this recovery—tepid though it may be—is long in the tooth. If there is a future downturn, central banks have little leeway to cut rates or unleash further quantitative easing, not to mention the growing criticism of these policies in suppressing interest rates and driving asset bubbles.

Regardless of what choices it makes, the likelihood of the Bank of England being behind the curve and having limited room for manoeuvre is high. Markets also believe the same if the real yield curve—in other words, the perception of future yields after inflation—is to be believed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. UK implied real forward curve for gilts (Source: Bank of England)

Headwinds

For treasuries, this is what matters and what they have to plan around. For the next 40 years, the consensus is that investors will face a headwind of -1% to -1.5% per annum as they try to eke out returns. That means rethinking the makeup of the portfolio to increase yield, whilst being mindful of the enhanced credit risks that any interest rate rises portend. A holistic perspective is doubly important given the impact of wage inflation on the balance sheet and pension liabilities.

At the same time, banks cannot be expected to provide succor. Many will be obsessing about the impact of Brexit both on their business models and their staff. The success of London as a financial centre has driven the UK economy over the last three decades and more, but it has also left it dangerously unbalanced.

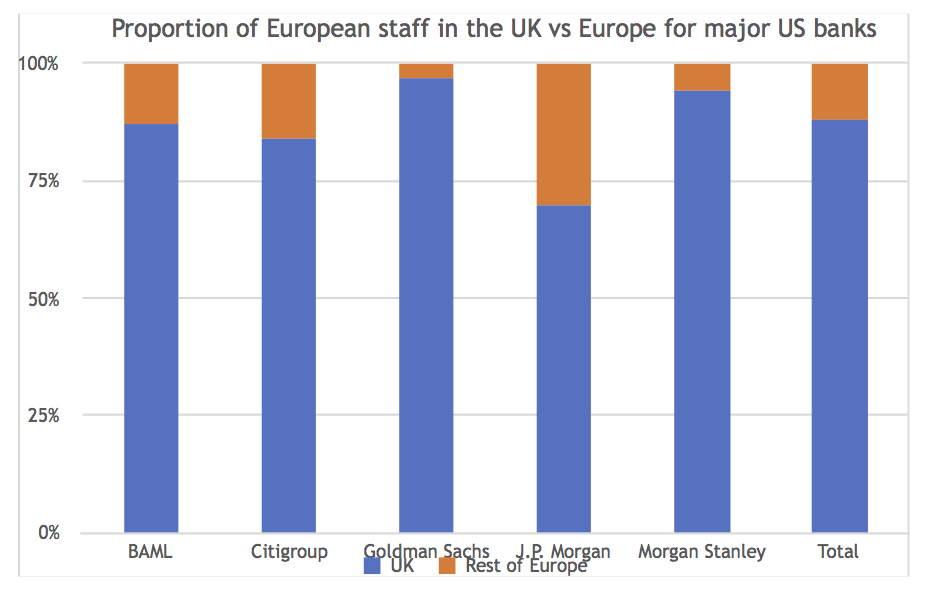

Figure 2. The proportion of European staff in the UK versus elsewhere for major US banks. (Source: Bruegel)

Today, for the major US banks, almost 9 in 10 of their European employees sit in London (see figure 2). Any attempt to reshape the financial servicing of Europe will inevitably mean job losses and moves outwards into the mainland. It will also mean a relative lessening of the importance of London to their European operations. The uncertainty of Brexit—across regulation, jobs, profit margins and the like—resonates just as strongly for them. And though few will have sympathy for their plight, it is important to understand that the financial system in the UK has become that little bit more fragile and that little bit more inward looking.

For treasuries, coupled with the travails of MiFID II, that also means that getting their accreditation as professional investors is doubly important as well as expanding their horizons past the simple medium of credit ratings. The alphabet cannot capture these uncertainties and the best defence lies in dynamism and diversification.

The investment returns born of Brexit may be small, and the risks large. Like the farmer tilling his fields year after year, we can alternately curse the gods on high and pray for clement weather. But like the farmer born of experience, we can also watch the signs carefully and plan our crops accordingly, taking control where we can. It does not always guarantee a good harvest but it certainly improves the odds over time.

Dr Bob Swarup is Principal at Camdor Global Advisors, a macroeconomic, investment and risk advisory firm focused on helping local authorities innovate to meet today’s unique challenges. He may be contacted at swarup@camdorglobal.com.