Sponsored Article: Markets currently enjoy a period of low volatility. Is this the calm before the storm? A more measured way of seeing volatility, whether high or low, may be as a story about the past rather than a guide to the future.

A quick perusal of the financial news will alert viewers to one of the most prominent financial market bogeymen of our time: low volatility. To the casual observer, worrying about the absence of sharp movements in asset prices might seem odd, but for many market insiders, recent placid financial conditions represent the calm before the storm.

A quick perusal of the financial news will alert viewers to one of the most prominent financial market bogeymen of our time: low volatility. To the casual observer, worrying about the absence of sharp movements in asset prices might seem odd, but for many market insiders, recent placid financial conditions represent the calm before the storm.

One popular measure of volatility, the VIX, also known as the “fear index,” measures equity market volatility anticipated in the next 30-days. And guess what? Equity investors expect little volatility ahead. In fact, since the VIX series began in 1990, there have been 54 days where the index read below 10. Half of those sub-10 VIX days occurred in 2017 alone.

Before you jump to conclusions about volatility, we must first explain what volatility is and identify possible suspects that explain the minimal market choppiness. Further, we ask, do volatility readings give us any insight into the future of the markets? In the end, we find that current volatility does not actually give us much insight into the future.

Define the Crime and Round Up the (Un)usual Suspects

A good detective begins work by first understanding the mystery at hand. As we open the books on this case, we do the same for volatility.

The VIX measures how much the participants in the market expect the S&P 500 to vary in the next year (see What Is the VIX? box below). Historical volatility is just a measure of the movement in the price of an underlying security (e.g., oil price, the price of the S&P 500 index, or an individual stock) over a given past period.

While the financial media speak of the VIX most often, the low volatility environment extends across markets and asset classes. For example, in the fixed income market a less-well-known measure, the MOVE index, has also touched the lowest levels since the crisis ended.(1) Commodity volatility, such as oil price gyrations, are also at lows compared to the post-crisis average.

What Is the VIX?

A (call) option is an option — but not an obligation — to buy an asset at a future date at a specified price.Despite centuries of options trading, until the 1960s a rational framework for pricing options did not exist. Not until the Black-Scholes equation came along, that is.

The equation uses the exercise price of the option, the current price of the underlying asset, the time to expiration, and the implied (future) volatility of the underlying security, to estimate the price of an option.

To create the Cboe Volatility Index, also known as the VIX, Cboe Global Markets (the largest options exchange in the world) looks at the implied volatilities of different options on the S&P 500 and calculates a weighted average.

The idea is that if options prices suddenly change, and we know the rest of the factors, we can determine the volatility traders are “pricing in” — thus, a fear gauge is born.

Implied future volatility based on the price of options in the market becomes the VIX. The VIX number tells us how much the participants in the market expect the S&P 500 to vary in the next year (+/- 9.77% at the start of 2018).

Now that we have defined the mystery at hand, let’s identify some possible suspects behind low volatility.

Market Volatility is Low Because Macroeconomic Volatility is Low

The first suspect is macroeconomic volatility–or the lack thereof. While financial market volatility garners all the press coverage, macroeconomic data volatility is also at record lows.

Consider the non-farm payroll employment report, one of the most widely watched gauges of the health of the labor market in the United States, which tabulates a monthly number of jobs lost or gained in the U.S. economy. The data tends to be volatile and can move dramatically due to one-off events (like hurricanes).

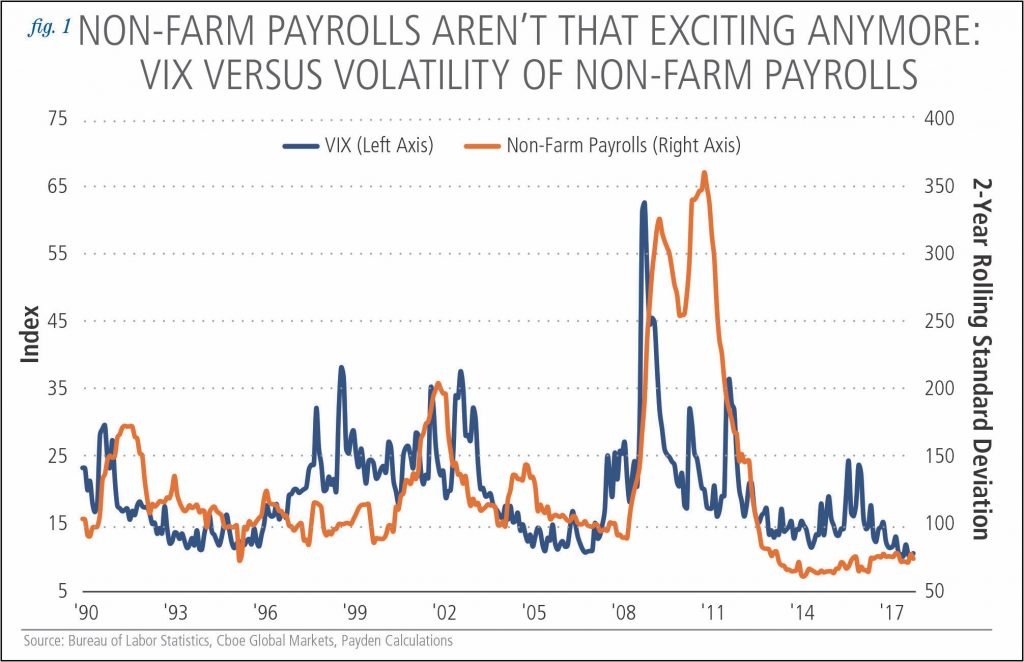

As can be expected, the non-farm payroll report was volatile during the financial crisis but since then has averaged 200,000 monthly jobs gains with little variability. In fact, non-farm payroll volatility during the last three years has been at all-time lows (see Figure 1).

The lack of macroeconomic volatility is not some fluke found in the monthly job numbers. Another key measure of economic activity, the quarterly gross domestic product (GDP) report, also shows record low volatility. Whether you want to call this the “Great Moderation” as the former head of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke once did, GDP growth figures do not swing as much as they used to in previous cycles.

So, why is macroeconomic volatility so low? As the composition of the U.S. economy has changed, so too has the volatility of output. For example, hiring has become more service-oriented and less susceptible to the “boom and bust” of goods manufacturing of decades past. Regardless of the causes, the absence of macroeconomic volatility is important to financial markets.

In a widely cited paper, International Monetary Fund (IMF) economists Olivier Blanchard and John Simon argued that the “absence of major adverse shocks over the last twenty years” was due to a “large underlying decline in output volatility.”(2) They noted that this decline was a steady one that began as far back as 1950 and decreased volatility by a factor of three, which was “more than enough to account for the increased length of expansions.” They wrote this paper in 2001, and since then output volatility has declined even further. After picking up during the crisis, output volatility declined to its lowest level ever during Q3 2017 (see Figure 2 below).

Less Active, More Passive

Another likely suspect behind low volatility readings is the rise of passive investing. As passive managers control more and more assets, they will trade less by design. In fact, as of 2016, passive mutual funds and ETFs together held a 10% or higher stake in 458 out of 500 companies in the S&P 500 index, compared to just two companies in 2005.(3)

In the U.S. Treasury market, another passive player has emerged. Of the $4.5trn constituting the Fed’s balance sheet, more than half is represented by U.S. Treasury bonds.

Since the Fed does not trade bonds but passively squirrels them away, it comes as no surprise that the MOVE index (which is effectively the VIX for the U.S. Treasury market) has also been very low since the end of the financial crisis.

Many other central banks have also joined the action, passively accumulating assets they are highly unlikely to sell. The central banks of U.S., Europe, and Japan alone hold more than $14 trillion in assets. While the Fed recently announced an unwind of its balance sheet, and the European Central Bank is expected to do so soon, the pace of unwinding will probably be too slow to impact volatility–by design.

More Transparent and Less Volatile?

The role of behemoth central bank balance sheets goes beyond passive portfolio holdings. Evidence also shows that increased central bank transparency leads to lower interest rate and stock market volatility.

Data analysed for 40 countries between 1998 and 2005 showed that moving “towards monetary policy transparency is recommended, as stock market volatility can be reduced considerably.”(4) Another researcher found that “higher transparency improves the accuracy of interest rate forecasts for three months ahead and reduces rate volatility.”(5)

The Federal Reserve and other central banks have become much more transparent over time. In fact, before 1994 the Fed did not even publish its target federal funds rate.

By 2005, the Fed reduced the time between meetings and published minutes within three weeks. By 2011, they were releasing projections by individual members (the “Dot Plot”) and even–gasp!–holding press conferences. According to Dincer and Eichengreen’s index of central bank transparency, which rates central banks on a scale from 1 to 15, the Fed’s transparency index increased from 8.5 in 1998 to 12 in 2014.(6)

In fact, Dincer and Eichengreen found that this was a global phenomenon. Of the 120 central banks studied, only one central bank is less transparent than it was in 1998 (we’re talking to you, Uruguay). No wonder that market and interest rate volatility have fallen. Investors have a much better sense of what central bankers are doing and are less “surprised” by their decisions.

What, Us Worry?

While there might be reasons why volatility is so low, we still must reckon with the “this is the calm before the storm” concern. After all, a period of low volatility is always followed by a recession, right? Or, in the famous words of economist Hyman Minsky, “stability is destabilizing”?

Not so fast. New York Fed researchers looked at stock market returns and volatility measures going all the way back to 1926. The result? Current volatility readings do not give us any insight into volatility 12 months, or even one month, from now.

The New York Fed expanded their analysis to determine whether periods of “extremely low” volatility (like the one we are in right now) made the market more likely to “jump” into a period of high volatility. They found that the probability of going into a period of high volatility was the same whether we are in a period of “extremely low” or “normal” volatility.(7)

Who You Calling “Complacent”?

Investors who are still worried about volatility as a sign of complacency in the markets would be better served by looking at the SKEW index. The SKEW index, also published by Cboe, looks at how much more is being paid for options to protect against downside risk compared to options purchased for upside bets.(8)

Whereas the VIX looks at the implied volatility of all options, the SKEW is another way of assessing fear in investors. If investors were overwhelmingly complacent, they would not be “paying up” for protection against adverse outcomes. Instead, the SKEW index has moved higher in an almost linear fashion since the crisis ended. Complacent? Think again. If anything, many investors are thinking about downward moves.

Murder on the Orient Express

In sum, while investors and observers are fond of pointing to low measured financial market volatility and jumping to conclusions about the future, we caution against such an approach. Just as in Agatha Christie’s novel, Murder on the Orient Express, wherein famed detective Hercule Poirot found all the passengers on the train involved in the crime, we see several likely culprits behind low volatility that go a long way to explaining financial market calm.

Chief among our favorite suspects is macroeconomic stability. Considering the list of suspects is an important exercise for investors, as it conveys the message that low volatility likely results from more than just the “central banks have done it” thesis.

What’s more, even if readers do not accept our argument that many culprits are at work to produce a low volatility environment, low volatility itself tells investors next to nothing about what the future holds. Volatility, low or high, might just be a better description of what has happened rather than providing any insight into what is to come.

Sources

1.According to Bloomberg, the Merrill Lynch Option Volatility Estimate (MOVE) Index is the weighted average on implied volatility of 1-month options for the 2-year, 5-year, 10-year and 30-year Treasury bonds.

2.Blanchard, Olivier J. and Simon, John A., The Long and Large Decline in U.S. Output Volatility (April 2001). MIT Dept. of Economics Working Paper No. 01-29.

3.Berman, Dennis K., & Jamie Heller (2016). “Wall Street’s “Do Nothing” Investing Revolution.” Wall Street Journal

4.Papadamou, S, Sidiropoulos, M. and Spyromitros, E. (2016) Central bank transparency and exchange rate volatility effects on inflation-output volatility, Economics and Business Letters, 5(4), 125-133.

5.Middeldorp, Menno (2011) Central Bank Transparency, the Accuracy of Professional Forecasts, and Interest Rate Volatility, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 496

6.Dincer, N. Nergiz and Eichengreen, Barry (2014), Central Bank Transparency and Independence: Updates and New Measures, International Journal of Central Banking

7.David Lucca, Daniel Roberts, and Peter Van Tassel, “The Low Volatility Puzzle: Is This Time Different?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), November 15, 2017.

8.Jean Boivin, “What low volatility is (and isn’t) telling us.” BlackRock Blog, September 8, 2017.

This article was first published in the latest edition of Payden&Rygel’s Point of View: Our Perspective on Issues Affecting Global Financial Markets.

Register for the Room151 LGPS Quarterly Newsletter