Sponsored Article: Is top-down government action the only way to address global environmental issues? Not at all. In fact, despite the focus on one global power’s exit from a key climate accord, a burgeoning, bottom-up movement is taking shape, with the bond market—yes, you read that right—leading the “green” charge.

President Donald Trump threatened to withdraw the United States from the Paris Climate Accord, but don’t think America has turned its back on the planet. Instead, a bottom-up response to environmental concerns is well underway, and the capital markets appear poised to play a crucial role in the effort. In particular, individual cities and corporations can support climate protection by issuing so-called “green bonds.”

President Donald Trump threatened to withdraw the United States from the Paris Climate Accord, but don’t think America has turned its back on the planet. Instead, a bottom-up response to environmental concerns is well underway, and the capital markets appear poised to play a crucial role in the effort. In particular, individual cities and corporations can support climate protection by issuing so-called “green bonds.”

As an investment manager, our goal is neither to support nor criticize the United States’ economic or climate policies. Instead, we intend to provide a lively introduction to the world of green bonds.

For those feeling a bit “green” when it comes to sustainable finance, let us clear up definitions first: a “green bond” is a financial instrument that signifies a commitment to use the proceeds to finance or refinance projects that deliver positive environmental impact. Green projects include, but are not limited to: renewable energy, clean transportation, sustainable land use, and energy efficiency.

Green bonds are well-suited for large-scale sustainability projects and enable cities, states and corporations to secure large amounts of capital. These “do-good” investments are becoming more popular as corporations and municipalities build brands around “sustainability”, and as fund managers increasingly create vehicles that direct capital toward these projects. Perhaps we should not be surprised by these trends: Millennials are nearly twice as likely to invest in funds that target environmental or social outcomes.(1)

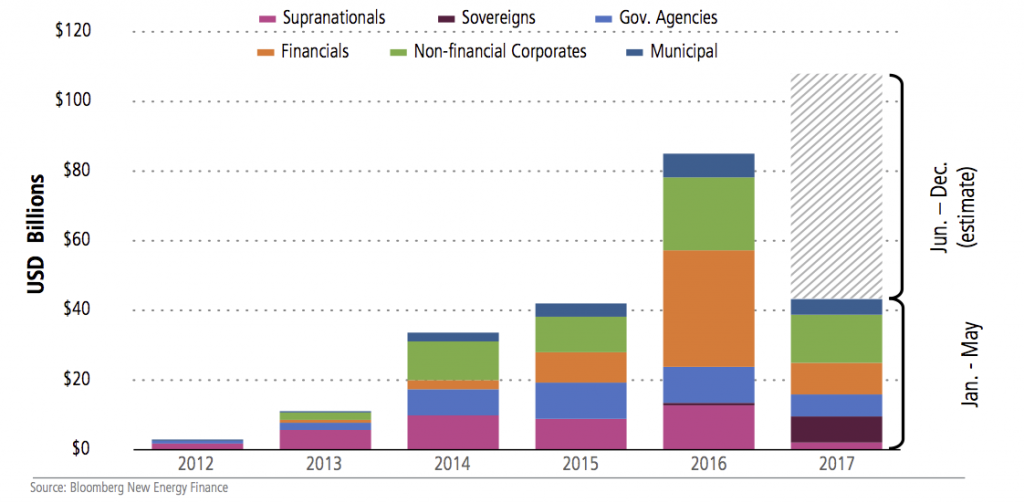

The issuance of the green bond market is expected to exceed USD 100 billion by the end of 2017 (see Fig. 1), though will remain small and immature, accounting for less than 1% of the worldwide bond market. We think green bonds can thrive as a key component of the bond market if a uniform definition is adopted and if investors keep a keen eye on the use of bond proceeds.

Going green: how green bonds started

Green bonds have only developed in the last decade, but they have been growing at a fast pace. In 2007, the European Investment Bank issued the world’s first green bond, followed in 2008 by the World Bank. These multilateral development banks were the sole issuers of green bonds until the first corporate green bonds were issued in 2013 by EDF, Bank of America, and Vasakronan. Specifically labeled green bonds attract investors as the securities enable them to invest directly in sustainable projects. Corporations covet the “green” label as an opportunity to deliver sustainable narratives and to explicitly market their bonds as environmentally and socially conscious investments.

The green bond market expanded greatly in 2015 when 195 countries signed the Paris Agreement—a commitment to cut emission levels and to hold the increase in global average temperature below two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.(2)

To meet the aggressive temperature goal by 2030, an estimated $93trn in infrastructure investment is needed. In response, many cities and municipalities around the world turned to debt financing for low-carbon development projects, especially for renewable energy infrastructure. As of February 2016, green bonds have been issued in 23 currencies and 14 markets of the G20.(3)

Did you know?

California, New York, and Massachusetts issued the largest amount of green municipal bonds, with California leading the charge. However, on average, green municipal bonds by state only constitute 0.6% of the total outstanding municipal bonds. Vermont is the greenest state regarding the total amount of outstanding green municipal bonds. The proceeds of the most recent green bonds issued by the Vermont Municipal Bond Bank are expected to be used to install energy-saving equipment, including water heating and heating control systems.

As a result, by the end of 2016, global green bond issuance more than doubled from one year prior, with nearly $97bn in fresh financing. China accounted for $32bn, as one of the leading countries issuing green bonds.(4) Approximately 40% of the proceeds from new issuance financed clean energy, while nearly 25% went to buildings and industry, and around 10% to transport.(5)

As for 2017, the total green bond issuance haul year-to-date (as of May 5th, 2017) reached $45bn, putting the market on track to best its 2016 total and reach $111bn by year end.(6)

There is a growing trend for green projects, as more institutions support initiatives aimed at preserving the environment. However, the green bond trend goes beyond recent climate initiatives. Emerging markets, in particular, face a growing need for energy-efficient and clean technology. As the cost of constructing clean tech infrastructure falls, countries are shifting towards renewable energy. For example, in South Korea, newly-elected President Moon temporarily shut down all coal power plants and mandated more investment in renewable energy power plants as Seoul, the country’s capital has recently become one of the world’s most polluted cities.

Some emerging markets still do not have a strong banking or capital markets foundation to help finance high-cost infrastructure projects. In the energy sector, countries with the greatest need for power plants are the ones that rely heavily on international financing. These countries issue project-specific green bonds backed by single or multiple projects to finance high-cost projects. For example, the Philippines financed a geothermal power plant by issuing green bonds, the first local currency green bond in the power sector. By issuing green bonds, emerging economies can enhance the growth of their debt markets and reduce the infrastructure-investment gap.

Green bonds marry municipal bonds: green municipal bonds

The US lags the rest of the world when it comes to green bond issuance. Green bonds comprised a mere 0.061% of the total US bond market, a smaller share than that of China, India, and many European nations. The slow pace of development is due to relatively small offering sizes and sporadic deal flow, which leads to a lack of liquidity and stunted growth of the market. Demand also remains mostly retail-driven, through SRI (Social Responsible Investing) funds.

In the US, green bonds are most intimately related to municipal bonds, both regarding features and issuance, as most green projects are financing renewable energy power plant and energy-efficient transportation. Similar to the US municipal bond market, key investors for green bonds are individual municipal bond investors who seek tax-exempted income. A growing number of investors, who tend to be of the “buy-and-hold” variety, span a wide range including institu- tional clients to individual investors.

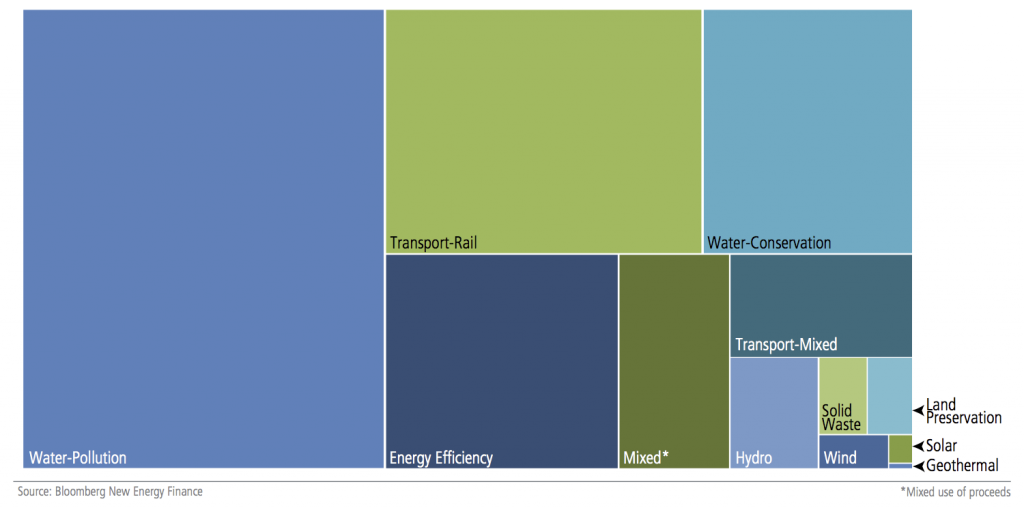

Over $3.7bn worth of new municipal green bonds were issued in the second quarter of 2017, making one of the busiest quarters of municipal activity (Q1 2017 saw $1.5bn in issuance). As long as the current pace of green municipal bond issuance continues throughout the year, it is estimated that annual

green municipal bond issuance will hit $10.4bn in 2017, according to Bloomberg. State-run entities like infrastructure and public transportation entities are the largest issuers, and green municipal bonds are mostly used for managing water-pollution and rail transportation (see Fig. 2).

Challenges: Shades of green

The overall purpose of a green bond sounds great—it facilitates financing for long-term, capital-intensive infrastructure projects and encourages people to be aware of the environment. However, at the same time, green bonds face critical challenges to enhance market transparency.

One of the market barriers is that there is no universal definition and standard for green bonds. Try and evaluate the “greenness” of a bond from the following two examples:

—The City of Long Beach, California, issued bonds to pay and/or reimburse the Harbor Department for capital expenditures incurred or to be incurred at the Port of Long Beach. This bond is considered “green” because the proceeds are expected to be used to reduce air emissions at the port by reducing the number of trucks.

- Why does the City of Long Beach need financing when it is not adding but rather reducing required facilities? Does “reducing the number of trucks” count as a green project? Can investors accurately monitor changes in emissions around the port?

—The Maryland Economic Development Corporation self-labeled its bond as green bonds based on the Green Bond Principles. The Issuer believes that its project is green because it results in a 16.2-mile light rail transit line that falls under“clean transportation” category.

- Since green bonds can be self-labeled, how reliable is this “green” label? What makes a project green?

Likewise, different countries have their distinct definitions, challenging the green bond market to conform to a common understanding. This self-labeled “green” has broad meanings that confuse investors and put issuers at risk of “greenwashing,” which is using the proceeds from green bonds for non-green uses. China, for example, counts clean coal as “green.” For these reasons, investors should be cautious when evaluating the“greenness” of a bond.

One solution to this issue may be to prompt all countries and corporations to adopt a single, rigorous definition of a green bond. However, if it were this simple, you might think: “Why did issuers not pursue this option in the first place? Do people even want to agree to a common definition?”

Issuers face the dilemma of either having a strict or loose definition of a green bond. A specific definition could limit market growth due to selectiveness but gives clarity on the use of proceeds to investors, whereas a “loose” standard would accomplish the opposite. Even knowing the potential downside of having a strict definition, to enhance the credibility of the “greenness” of a bond, we still believe having a unified and clear definition of the green bond is needed.

Challenges: Third party external “review”

Currently, the market is trying its best for transparency. Rating agencies such as Moody’s have promoted green bond ratings that assist investors in understanding overall risk factors. These third-party external reviews help investors verify the requirements of the Green Bond Principles of a bond.

However, the third-party verification process is still in its infancy. As of October 2015, only 60% of total green bond issuance was officially audited by a third party.(7) Also, the third-party verification process is costly, with prices that range from $10,000 to $100,000.(8)

Ratings reviews, like green bonds themselves, bring different approaches for assessment from each rating agency. Each reviewer has her own standard and criteria, challenging investors’ ability to effectively compare and measure.

Learning from FASB (Financial Accounting Standards Board), with its goal to improve financial accounting and reporting standards for investors, SASB (Sustainability Accounting Standards Board) was founded in 2011 with a similar purpose but with a focus on material sustainability features. SASB addresses public companies’ disclosure of material, reliable, and comparable data to investors so that they can make decisions with an awareness of environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors. This helps investors to assess a company in a comparable, rigorous way.

Why not apply this to fixed income? The external reviewer should review the “greenness” of a bond based on a common and well-structured standard created by an independent third party. Such a development will enhance the transparency and quality of the green bond market, boosting market growth.

Clarity brings serenity

By 2020, it is estimated that green bonds could enable $120bn in incremental annual investment.(9) As long as there is uniformity in the definition of “green” and rigorous evaluation of the use of proceeds, green municipal bonds have a high potential for further growth and transparency, becoming more diversified across geography and credit quality while targeting a wide range of investors. Cities and states may have their way on climate initiatives whether or not the federal government supports it.

This article was first published in the Autumn 2017 edition of Payden&Rygel’s Point of View: Our Perspective on Issues Affecting Global Financial Markets.

Sources

(1) Ernst & Young (2017), Sustainable investing: the millennial investor.

(2) Framework Convention on Climate Change, United Nations. 2017. “The Paris Agreement.” Accessed June 13th. http://unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9485.phphttp:// unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9485.php

(3) OECD (2015), Green bonds mobilizing the debt capital markets for a low-carbon transition, December.

(4) “Green bonds channel private-sector funding to the climate,” Economist, June 8, 2017. http://www.economist.com/news/ finance-and-economics/21723138-questions-persist-about- proliferation-green-standards-green-bonds?frsc=dg%7Ce

(5) Ibid.

(6) Bloomberg New Energy Finance (2017), Green bonds monthly, May.

(7) Ibid.

(8) Ibid.

(9) Bank of America Merrill Lynch (2015),