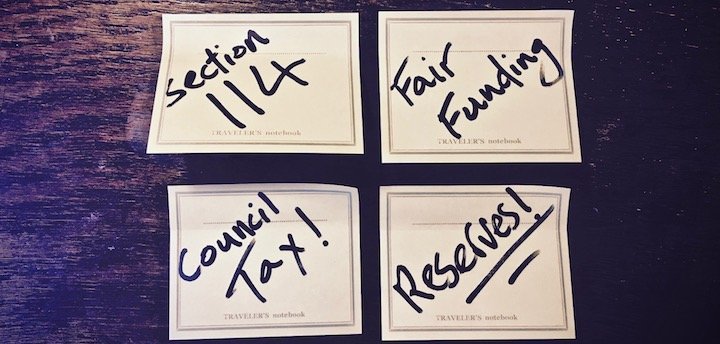

Local government last week saw the final financial settlement. Dan Bates analyses the underlying issues revealing a council tax system that is fragile and dwindling reserves.

Last week’s final finance settlement capped off a week where local government finances consistently made national headlines.

This started when Northamptonshire County Council issued a Section 114 notice and the immediate imposition of spending controls. This may have had some bearing on the one day delay in the final settlement as it was reported that Phillip Hammond and Sajid Javid were locked in meetings with rural shire MPs to avoid a rebellion and potential defeat in the vote on the settlement.

So, when the written statement was issued on 6 February, it was no surprise when a further £166m was found to assist authorities, particularly with adult social care pressures, enough for the whole package to be voted through. The press then moved onto “inflation busting council tax hikes across the country” as the focus on local government funding intensified.

All of these headlines bring into sharp focus the financial health of local authorities. So, let’s have a look at some of the detail behind those headlines.

Back bench settlement rebellion quelled with extra £150m

The provisional settlement was the third year of the four year deal announced in February 2016 which saw another billion pounds wiped from the settlement funding assessment (SFA) across England. That’s 6.36% between 2017/18 and 2018/19. By the end of the four year deal, SFA will have been cut by 32.24%, almost £7bn.

The additional £150m for adult social care and £16m for rural services isn’t a big sum in the context of these cuts. As the headline suggests, the extra cash was almost certainly a result of the threatened backbench rebellion led by Shropshire MP Daniel Kawczynski on behalf of rural Shire counties.

The extra £150m of adult social care funding was distributed using the 2013/14 Adult Social Care Relative Needs Formula which actually allocates slightly more per capita to the London boroughs and Mets, and not to the Shires which might not have, by itself, been enough to stall the threatened rebellion.

However, the additional £16m of rural funding provided a top-up which meant that the Shires received a slightly better share of the allocation and the vote got through.

Other than that, there weren’t any other big surprises in the settlement. The Government re-iterated its promise to look at negative RSG and corrected top-ups and tariffs were confirmed after the errors in Valuation Office data were revealed in the provisional settlement information.

Inflation-busting council tax rises of £100, or more

The dust hadn’t settled on the settlement headlines when attention turned to local authorities setting council tax up and down the country. Research by the Local Government Information Unit (LGIU) revealed, not surprisingly, that nearly all councils intend to go for a maximum increase, up to 3% this year or as much as 6% for social care authorities.

What the headlines don’t necessarily tell us is about the increasingly fragile nature of a funding system increasingly underpinned by council tax revenues where an additional 1% on the bill results in significantly different increases in spending power across authorities.

There are two reasons for this. Council tax band D levels vary significantly. For instance, the highest district band D is more than four times the level of the lowest (£341.46 compared with £80.46). Both these districts are receiving significant cuts to their government funding. But the higher band D authority is able to raise two and a half times more resources with a 3% increase than the low band D authority can with its £5 increase. Similar variations occur in the upper tier.

Average is rarely an average

The fact that we all express our taxbase in band D equivalents doesn’t make this the average. By way of example, 60% of Leicester City Council’s properties are band A, whereas in Richmond Upon Thames less than 1% sit in band A and 57% of properties are banded between bands E and H.

This means that an additional 1% on council tax brings in more than double per capita in Richmond than it does in Leicester.

The funding formulae has a correcting methodology for council tax differentials called the resources block, whereby councils with higher tax bases receive larger reductions to government funding to take account of these additional council tax incomes.

However, this auto-correction feature was frozen between 2013/14 and 2016/17 meaning that those lower tax base authorities suffered heavily in terms of spending power reductions.

So, given the fragilty of the council tax system, combined with severe cuts in central funding and relentless pressures on social care, it was only ever going to be a matter of time before the perfect storm hit. No longer a question of “if”, rather “when” and “where”?

Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire issued its section 114 report on 2 February and restricted spending to statutory services and those for vulnerable people. There is a lot which you can read about this, so I will offer you just a few facts.

- Like all authorities, Northamptonshire has suffered severe cuts in government funding. Between 2015/16 and 2019/20, it will have its SFA reduced by 39%, higher than the 32% England average.

- Spending power per head average, at £604 per head, is lower than the average for a Shire county with fire of £667, and much lower than the average for upper tier authorities.

- Northamptonshire has witnessed one of the highest increases in over 65 population between 2013 and 2016, no doubt adding to adult social care pressures, a frozen formula providing them with no recognition for these extra pressures.

- Over the last two years the council ran down its usable reserves by more than 50% indicating that reserves were being used to fund a budget gap; clearly an unsustainable position.

I have looked at the “movement in reserves” statement of all 352 local authorities and it is clear that Northamptonshire are not alone among upper tier authorities at using reserves to balance budgets.

About two thirds of upper tier authorities have depleted their usable reserves over the last two years. This fact alone is enough to indicate a funding system which is broken. If there is no new money available to the sector, it is likely that other social care authorities might follow on from Northamptonshire.

The Way Forward

The funding formulae will be taken out of the deep freeze in 2020/21 and the government is now consulting on a fair funding review. Consultation is currently live and will close on 12 March.

The fair funding review will help decide each authorities slice of the cake from 2020/21 and it is important that all authorities engage with this review and respond to the consultation.

However, perhaps it is more important that the whole of local government comes together to lobby for the overall size of the cake if local services are to be offered in a sustainable way over the next decade.

Dan Bates is an independent consultant with Pixel Financial Management.

@danatpixel