In the wake of the Northamptonshire saga and the ensuing speculation around various authorities’ well-being, Pixel’s Dan Bates sets out his vision of the quantitative metrics and qualitative analysis that should go in to assessing a council’s financial resilience.

There doesn’t seem to be a day that goes by recently without another authority hitting the headlines in relation to its financial sustainability. Ever since the Northamptonshire S114 declarations, speculation has been rife as to whether others are set to follow and a spate of external audit qualified VFM conclusions has thrown up an array of candidates.

Last month the Public Accounts Committee concluded that MHCLG does not understand, and is not addressing, the issue of financial sustainability of local government and CIPFA issued a consultation document on their proposal for an index of financial resilience for English Councils to a mixed response from the sector.

So how should we go about measuring financial resilience and sustainability?

It’s not just about the numbers

Any comparative analysis necessarily has to be focussed around numbers and averages and later I will suggest some measures which reflect resilience and financial sustainability. But, firstly, we shouldn’t forget the importance of organisational culture. A good organisation understands its financial position and has processes for considering financial sustainability as part of decision making. This is reflected in the responsibilities, attitudes and behaviours of elected members and staff and is clear from regular financial and performance monitoring reports.

Housing & Regeneration Finance Summit

October 31, 2018, London Stock Exchange CFOs/Treasurers/Investors/CEOs

Local Government – Housing Associations – Institutional Investors – Developers

Although organisational culture is more difficult to pin down and score for an index, it is clearly important. The Northamptonshire best value inspection report pointed to failings in processes which led to a lack of organisational awareness of the financial position brought about by confused structures, inadequate reporting and limited management challenge.

So maybe we should start with a more qualitative assessment of our processes. How aware are we of our financial position in the context of diminishing funding and growing pressures? Do we have adequate plans and do we report against these? Is financial stewardship embedded throughout the organisation?

Beware of data quality

Some of the recent headlines on financial resilience have surprised me and I can’t help feeling that speculation about which authority will be the next Northamptonshire has led to some misleading stories.

Any national level comparative reporting on financial resilience must be credible both in terms of the measures selected and in the data quality of those chosen measures. Quite a few stories lately have used revenue expenditure and outturn analyses (referred to as RA and RO returns). These unaudited returns, in my opinion, currently suffer from poor levels of data quality. At best, they are inconsistently completed across different authorities and at worst, they are simply inaccurate.

So whilst it is important to include the right measures to reflect resilience, it is just as important to ensure that the data collected for each measure is accurate and consistent.

How can we measure financial resilience?

How can we measure financial resilience?

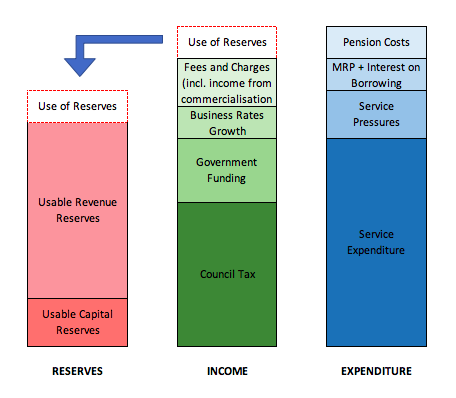

There has been a lot of focus, rightly so, on usable revenue reserves both in terms of actual level and annual change in the levels as measures of resilience. Northamptonshire at the point of their first s114 had seen significant year on year depletion in reserves to a point where it had almost run out. At Pixel, our annual review of reserves shows that there are real signs of financial stress, both at individual authority and types of authority level, brought on by funding reductions and demographic cost pressures.

A few of points on reserves:

- We need to be careful to distinguish between planned and unplanned use of reserves. It is quite possible that an authority is using reserves as a transitional arrangement as it moves to a new way of working that is financially sustainable. Additionally, our work has shown that some authorities have operated effectively for years with lower levels of reserves. In both cases, it is important that any index doesn’t unfairly misstate the position of such authorities and that any quantitative measure allows for some contextual explanation of the numbers.

- When I looked to compare reserves levels in audited accounts with RA/RO returns, I was unable to reconcile the two sources in over a quarter of all authorities. As accounts are audited and RA/RO are not, I would counsel against the latter’s use in any published comparative analysis.

- There is no doubt that reserves provide an important pointer of financial health but they are, after all, a product of incomes and expenditures and it is just as important, when considering resilience, to look at these factors. In the diagram above, I have set out the income and expenditure factors that I think are worth exploring for potential inclusion in a basket of resilience indicators.

Income

The speed and severity of funding cuts has clearly led to a depletion in reserves across most types of authorities since 2013/14 and the differing levels of reliance on funding and other income sources can point to comparative vulnerability of an authority to current funding mechanisms.

I would consider the following in any measurement of financial resilience:

- Relative reliance on council tax and government funding – high needs, low taxbase authorities will continue to be more vulnerable to future funding cuts. The Fair Funding review might change funding significantly. In my opinion, districts might lose out significantly in this review as the system is tweaked to reflect social care pressures and to ensure that counties receive a fairer share of both business rates growth and New Homes Bonus.

- Business rates growth –non-pilot authorities with little prospect of growth are likely to be more vulnerable to a system which the IFS has shown to be highly redistributive.

- Other incomes – whether from existing assets, such as car park or retail income, or from commercial investment, such as that undertaken by Spelthorne.

Expenditure

Control of expenditure to meet funding reductions has a significant bearing on the level of reserves required to balance budgets. This might be through the planned use of reserves as a temporary measure to bridge a budget gap or the unplanned use to fund unanticipated overspends. Effective processes are required both to plan and execute reductions in expenditure. In the case of Northamptonshire, the inspection report cited significant weaknesses in the control of expenditure which resulted in both planned and unplanned depletions in reserves.

It is more difficult to find datasets to measure expenditure in a consistent way across authorities but this is what I would propose:

- Budgeted use of reserves – should provide a measure of whether the authority is planning to live within its means.

- Revenue Outturn – taken from annual accounts, rather than RO forms, should indicate whether the authority has control over its expenditure and, in particular, its cost pressures.

- Comparative expenditure levels – should give an indication of where an authority might have higher than average levels of expenditure and be more vulnerable and therefore less resilient to demand led, demographic cost pressures.

- Costs of capital expenditure – often overlooked, in my opinion, but as funding is falling, those authorities with high capital financing requirements and external borrowing might find that their minimum revenue provision and interest costs are starting to account for uncomfortably larger proportions of their revenue budget.

- Pensions costs – another interesting one – our accounts review has revealed some staggering pension liabilities. As we all live longer and authorities have fewer staff paying into pension funds, larger annual payments to recover deficits may have a greater call on scarce resources.

These are the measures that I would seek to develop in a comparative financial resilience analysis. I would make the point that they are indicators and as such they give an indication and not an absolute measure of financial stress. We need to take care not to overreact to any one indicator but rather seek to understand what we are seeing in a wider context and by comparing with other authorities as well as considering changes over time and direction of travel.

You may agree or disagree with these measures or propose other indicators. Whatever your views, you should take the opportunity offered by CIPFA who are consulting on a Financial Resilience Index. The consultation closes on 24 August.