Tom Harris, UK local government research officer at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, makes the case for income tax devolution.

With Westminster in turmoil over how (and whether) to ‘take back control’ from Brussels, calls for the government to devolve more control over tax and public services to county and city halls have been struggling to gain traction.

Just three years ago things seemed different. George Osborne had pledged a “devolution revolution” with financially self-sufficient local government. Of course, the centrepiece of these plans – 100% business rates retention – didn’t survive the post-Brexit political fallout. And there is growing talk that the watered down plans (75% retention and the ‘Fair Funding Review’) may themselves be fudged.

In this context, the conclusion from our latest report on local government finance – that a local income tax would be the best option if we wanted to resurrect plans to devolve significant additional revenues to councils – may seem bold to say the least.

But hear us out.

Would a local income tax be an answer to the demands for local control and local incentives?

Given the scale of income tax revenues relative to councils’ existing spending needs, it would be unreasonable to consider full devolution. Instead, the most logical option would be to allow councils to control only a portion of the income tax schedule.

Even such partial devolution could bring in a lot of money. Our estimates suggest that each 1% of a local income tax on all tax bands would raise about £6 billion across England. In comparison, other ideas being discussed, like a tourist tax, would raise only a fraction of this. It’s also a buoyant tax: revenues would grow with inflation and incomes over time, without the need for manual increases like council tax.

In addition, allowing councils to keep a portion of income tax would provide them with a clear financial incentive to boost the incomes of local residents. That could mean increasing the number and quality of jobs in local areas – but also investing in skills and transport links to access opportunities in neighbouring areas. And unlike business rates, all local income taxpayers would have the right to vote in local elections, allowing them to hold councils to account for the tax rates set.

This would allow for more variation across councils according to local preferences. For example, Surrey might choose to set higher tax rates to fund higher quality services. Slough, on the other hand, might choose to set lower tax rates to attract new taxpayers, boost consumer spending and support local economic development. This kind of local flexibility might be exactly what councils are after.

But, would there be any difficulties?

While it would be much easier to localise than VAT or corporation tax, administering a local income tax would also bring challenges.

In particular, HMRC doesn’t currently know where all taxpayers live, as there is no statutory duty to provide this information. That would have to change. In addition, while being less mobile than sales and profits, people can move between areas, and tax rates could be a factor in their location choices. Yet, restricting councils’ powers to levy a flat-rate income tax, as discussed above, would limit the distortions associated with this. Ultimately, this would mean that councils couldn’t jack up or cut taxes on their highest income residents, for instance, without changing them for everyone else.

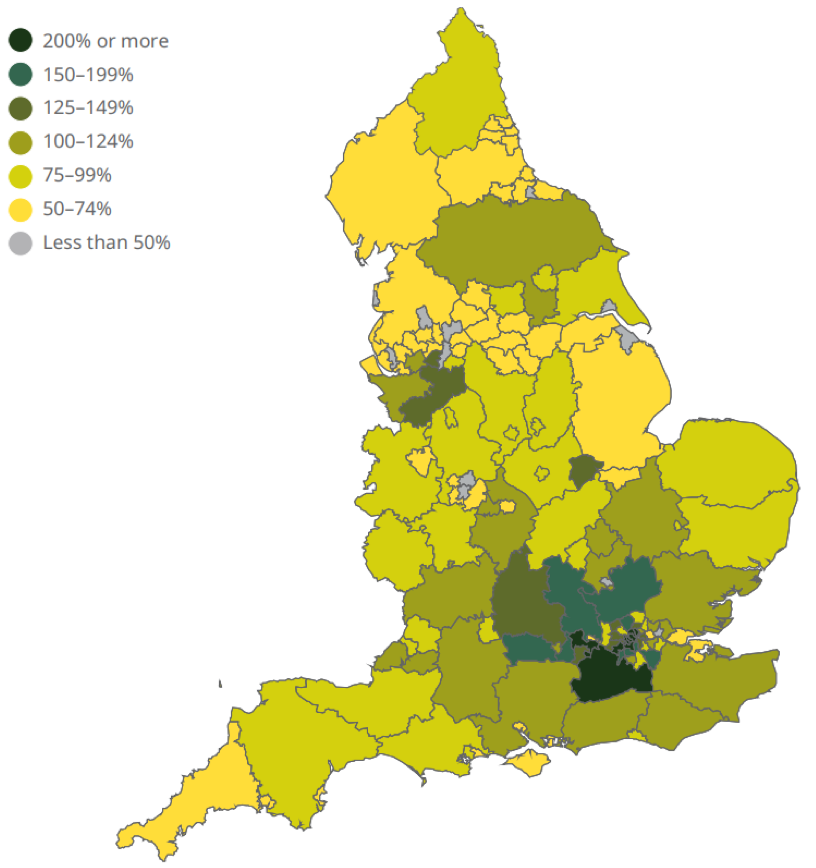

However, even if councils were only allowed to levy a flat-rate tax, there would still be substantial inequalities in revenue across areas – as shown in the map below. For example, many richer parts of west London would raise more than six times the amount that could be raised in councils like Hull and Leicester.

Left unchecked, this could result in large disparities in service provision between areas. This means there would likely need to be a system to redistribute these revenues between councils. But as we’ve seen with the existing grant allocation process, determining such redistribution is itself a tricky task.

Revenues per person from a flat-rate local income tax, share of national average (%)

More local control, but what about councils’ funding woes?

In the end, a local income tax would involve a trade-off between more local control and stronger incentives on the one hand; and the risk of the funding divergences these might entail on the other.

But if tax devolution is seen by councils as a way to increase their funding, they may be disappointed. A local income tax would not be a free lunch. Either national rates would need to be cut to make ‘room’ for the local rate, potentially meaning there would be less to spend on nationally-funded services like the NHS, or a local surtax would have to be charged on top of existing rates – meaning a tax rise.

So, if we are truly to address councils’ funding woes, we need a debate about tax levels as much as about tax devolution.