Sponsored article: Ian Simm explores scenario analysis and how it might be configured to address climate change.

At the time of writing, the economic shock caused by Covid-19 is still with us. As we don’t know how the virus behaves over the longer term, it’s wise to use scenario analysis to consider a range of (potentially radically different) outcomes.

Given the many parallels between the Covid-19 challenge and climate change—including global impact, severity and uncertainty—it is no surprise that scenario analysis is an essential tool for assessing climate change, and work in this area has been underway for several years.

However, too much effort is currently being wasted developing highly complex scenarios that practitioners find impossible to use. What we need is consensus around scenarios based on “policy trajectories,” each of which can be mapped to a climate outcome, e.g., 2.5 degrees of warming on average, while being “easy to use” in financial models.

Widespread adoption of such scenarios should facilitate a dialogue with policy makers over the benefits to society of a commitment to long-term policy frameworks, particularly a lower cost of capital.

Ideal tool

We’re all used to dealing with uncertainty about the future: How will my life pan out? Will I achieve my career ambitions? How long will I stay healthy? Although most of us don’t consciously use scenario analysis to plan our personal lives by considering alternative possible outcomes, it is the ideal tool for considering possible futures for a business, a nation state or the planet.

Scenario analysis specialists are having a field day with climate change, with its potentially enormous impact, uncertain timescale and unclear consequences. Yet efforts to apply scenario analysis to decisions that need to be made now have created a high degree of complexity, typically requiring a long chain of assumptions that fail to address the question: “So, what do we do?”

For example, businesses and financial organisations are facing significant challenges implementing the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), which advocates the use of scenario analysis in its 2017 report.

Those without any previous experience of this technique often struggle to know where to start, while those with some experience often struggle with technical challenges, including how to develop realistic scenarios that can be used to assess impacts across multiple asset classes. Currently businesses, investors and governments alike appear to be left scratching their heads about how they should react.

Starting point

Couldn’t the whole thing be much simpler? Could we isolate a simple set of “climate change factors”, run scenarios for them and assume that all other drivers of change in society will adjust accordingly?

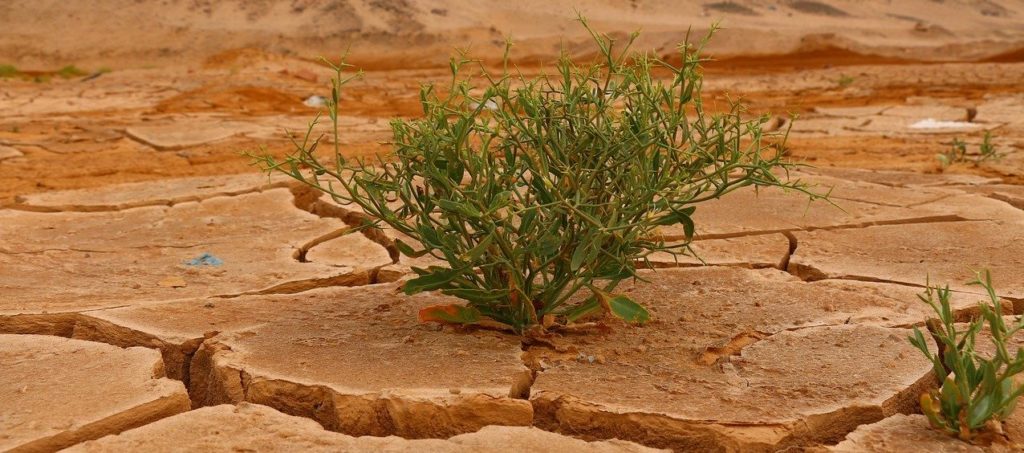

As noted by the TCFD and others, it clearly makes sense to assess climate change from two vantage points: The physical changes to the planet, including impacts on weather systems, sea levels and soil stability; and the transition path that society needs to follow to reduce our emissions and limit these impacts.

As a starting point, these need to be considered separately: As climate modelling improves, it’s foreseeable that scenarios for future environmental hazard at specific locations around the world can be generated, making the assessment of physical risk more manageable. Today, this type of information isn’t generally available given a lack of appropriate models, a dearth of cost-effective computing power and a shortage of skilled personnel.

At first sight, transition risk looks complex given the difficulties in predicting the interactions between policy goals and interventions, technology change and evolving consumer preferences.

Yet experience of environmental policy over the past fifty years has shown that, without direction or incentives set by government, consumers will overwhelmingly want to consume greater quantities of larger, more comfortable and, where applicable, faster products.

Consequently, I believe that the analysis of climate change transition needs to start with policy. We’ve seen this work well in the past, for example with the phasing out of lead in petrol (to eliminate horrific physiological damage), banning CFC refrigerants (to protect the ozone layer) and eco-labelling of white goods (to spur energy efficiency).

Policy trajectories

Looking to the future, the smart way to use scenario analysis to assess the potential impact of climate change transitions is through the articulation of “policy trajectories”, i.e., the mapping over time of how policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions of individual sectors will be introduced.

In practice, at the national level, environmental economists are able to indicate how a desired “end state” of emissions, for example “net zero” can be mapped back to a small number of policy trajectories, for the economy as a whole and for individual sectors.

More broadly, at a global level, the same approach can translate a target degree of planetary warming firstly to “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs), and thus back to desired policy trajectories at a national or regional level.

Now we’re getting somewhere. These policy trajectories can be most easily described in terms of carbon prices (through the introduction of taxes or equivalent “cap and trade” regimes). However, they could also be expressed in part, or in whole, as product standards (including bans).

If there were consensus around a specific set of possible policy trajectories for individual sectors and geographies, businesses could credibly describe both the impact of any specific scenario on their expected financial situation. For example, “a carbon price of XX by [date] is likely to impact our balance sheet by YY but also create the following opportunities…”. They could also articulate how robust their strategy is when examined against the range.

Implicit in these calculations will be analysis of the effect of policy on other factors, for example technology development, and assumptions around the evolution of other factors, for example changing consumer preferences.

In parallel, investors could check the analysis that companies produce in this area, while also applying their own probabilities to each scenario in order to estimate the “value at risk” of their investment. With investors being free to choose probabilities, or even to develop their own scenarios, a market price for this value-at-risk should emerge as investors express their views on the intrinsic value for companies whose shares are listed on stock exchanges

But it gets better. The market price for this value-at-risk will imply a risk premium for policy uncertainty, i.e., investors are seeking compensation for the lack of clarity; some relatively simple analysis should uncover a sensible estimate of this. By presenting this information to policy makers, it should be possible to demonstrate that policy uncertainty was leading to an unnecessarily high premium (or “cost of capital”), and that the transition to a low/zero carbon world was being held back. The “positive feedback” should help accelerate the adoption of clearer, longer-term policies.

Scenarios

So, how could this work in practice? In recent years, reputable sector and scientific groups such as the International Energy Agency and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have developed, published and updated scenarios describing the possible effects of climate change.

Although the current crop of scenarios is hard (or impossible) to use, it would be entirely plausible that these groups extend their expertise to develop scenarios based on policy trajectories, accessing additional skills as necessary.

With the COP26 conference in sight, it’s crucial that those leading the negotiations cut through complexity and advocate commitments and strategies that can really make a difference.

The logic is simple to explain: The global burden of reducing greenhouse gas emissions must be apportioned through NDCs; to be credible, NDCs must be backed up by viable policy roadmaps/trajectories (by sector); and with reliable, long-term policies in place, business and their financial backers should be confident to deploy capital at scale, thus catalysing the essential transformation to a zero carbon economy.

In the absence of clear policy trajectories, businesses and investors will be applying probabilities to a range of policy scenarios, inflating the cost of capital and holding back the essential transition. Governments hold the key to “saving the world” from climate change. But investors can help them by converging around scenarios that make this clear and can be used in the real world.

Ian Simm is founder and chief executive of Impax Asset Management.