Elizabeth M. Carey writes that LGPS funds should target levels above 100% before anyone begins to feel comfortably funded.

In an age when many people are living longer and healthier, it is often said that “60 is the new 40”. Longer, healthier lives are to be celebrated. When thinking about funding levels for LGPS funds, however, more years of healthy, LGPS pension funded retirement increase risks to current contributors as well as to future scheme joiners, who may not yet have taken up their job with an LGPS employer or current employees who may not yet have elected to join the scheme.

In light of macroeconomic uncertainties and the maturing age profile of LGPS membership, the question arises as to whether funds are sufficiently capitalised to ensure their long-term sustainability and affordability for all.

Room151’s LGPS Quarterly Webcast

Private markets

23 February 2022

Online

Register here for a free place if you work for an administering authority or pool

Deterministic vs. stochastic (aka multi-scenario) modelling for funding sufficiency

LGPS funding levels are calculated in a deterministic manner by comparing the value of fund assets versus the discounted present value of future benefits, including past and future service, inflationary increases, and projected years spent in retirement for current scheme members. While many of these factors can be forecast fairly reliably across a large number of members, some such as inflation cannot be so accurately predicted. Instead, assumptions are made about assets like equities or real estate, whose values are believed to correlate positively with inflation.

A variety of discount rates are used to calculate the present value of future liabilities. While the correct way to discount liabilities is widely debated (whether based on Gilt yields, inflation assumptions or projected annualised asset returns), one thing is near certain: the future will not turn out to match the deterministic projections used by actuaries, consultants and fund officers in calculating funding ratios. Asset values tend not to move in linear, favourable ways, while inflation can turn out to be higher than expected and have unpredictable knock-on effects.

Given the uncertainties of future liabilities, and asset values, a more realistic assessment of potential funding gaps should be considered.—Elizabeth Carey.

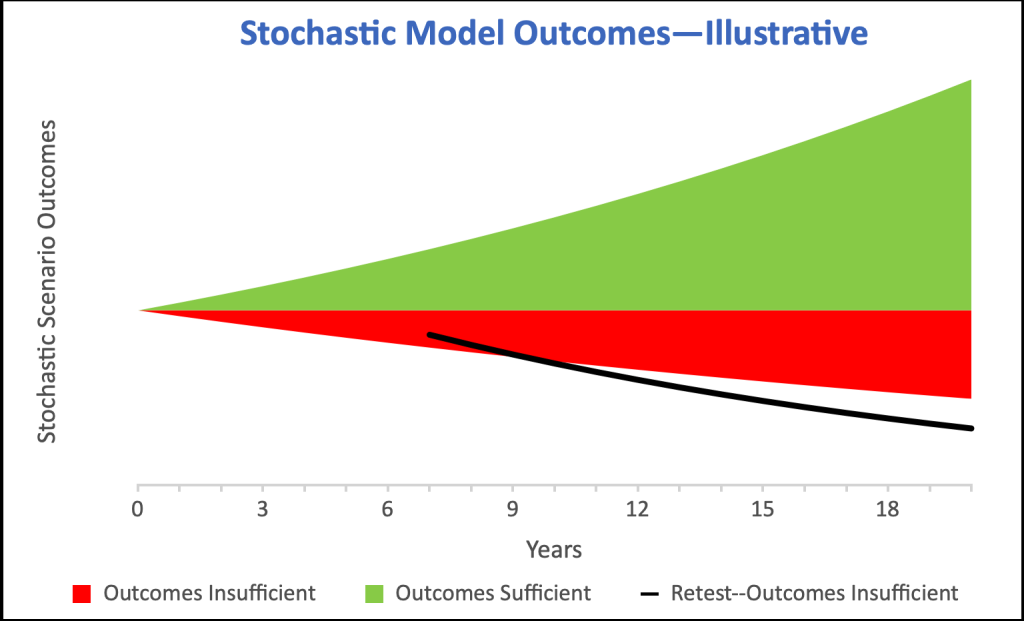

For this reason, many practitioners turn to stochastic models, which generate a very large number of scenarios with respect to interest rates, inflation, asset values and other factors. Sometimes called “Monte Carlo” simulations, the range of outcomes—some more positive and others more negative than the deterministic scenario—is arguably a better reflection of the range of possible outcomes based on a myriad of macroeconomic and market developments (See Chart A below).

Consultants often speak of the likelihood of being sufficiently funded based on projected pension promises as of the valuation date. A funding sufficiency likelihood of 60-70% is not uncommon, and means that 60-70% of the hundreds of pathways in the Monte Carlo model turned out sufficient to meet projected pension liabilities.

But that leaves a 30-40% likelihood that investment returns will be insufficient to meet liabilities. A combination of future active members, their employers or council tax payers would need to step in prospectively to fund shortfalls. This result would not be very fair from an intergenerational standpoint.

Chart A.

Since revaluations occur every three years, one should expect to re-run stochastic models regularly. Conceptually speaking, the starting point for a retest simulation should lie within the results of previous simulations.

If adverse macroeconomic or market developments meant that asset values had fallen below required levels, LGPS funds would be in a much more challenged funding position, from which a new series of potential pathways would need to be generated. In such a scenario, the probability of being underfunded could rise considerably from the 30-40% to well over 50% (see the black “Retest” line in Figure A above).

Large and looming risks pose challenges to reported funding levels

While many LGPS funds may start out at or near 100% funding ratios, adverse developments like the retrospective McCloud judgment or full GMP indexation increase risks to funding level sufficiency. Climate change is another large and looming risk whose effects remain largely unquantified. Prudence would suggest assuming further adverse changes over the multi-decade horizon of LGPS funds, and hence increasing capital bases.

Given the uncertainties of future liabilities, and asset values, a more realistic assessment of potential funding gaps should be considered.

One indication might be the difference between reported funding levels and IAS 26 funding ratios. The latter can be 25-50% lower than what is calculated using deterministic actuarial models. In other words, some of the calculated funding ratios used by LGPS funds could prove overstated, possibly by a large margin.

The challenge of shifting membership profile

One important, though often overlooked, source of funding risk is the evolution of the LGPS membership profile.

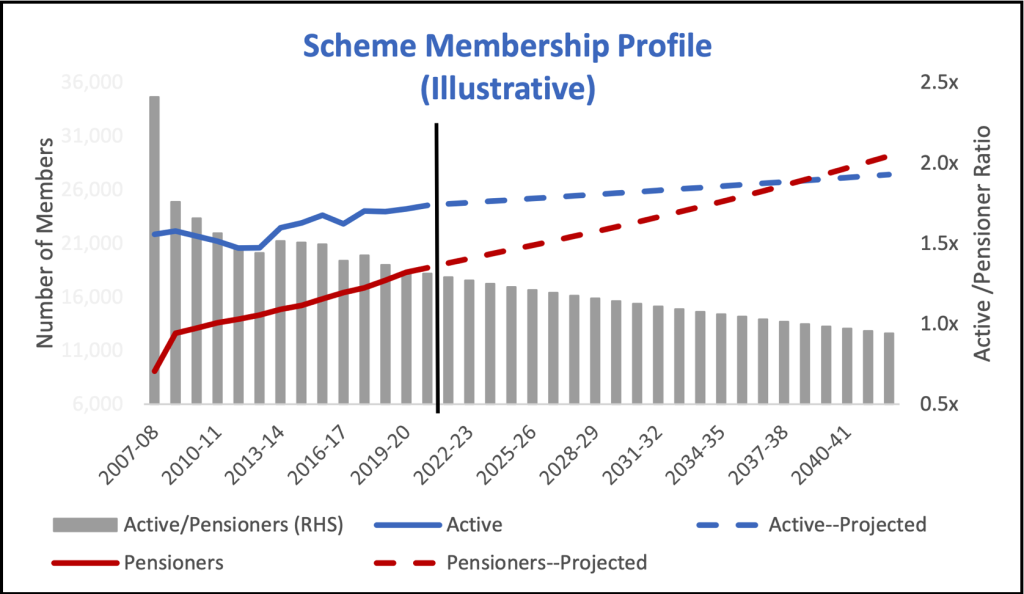

Considerable variation exists between LGPS funds, yet the past decade has seen the ratio of active (contributing) to retired (benefit receiving) members decline, driven by broader demographic trends, but accelerated by austerity measures following the Financial Crisis of 2007-8.

Every year fewer active members support each retiree (as illustrated by the Active/Pensioner ratio in Chart B below). With a large group of inactive but not yet retired (“deferred”) members, this relationship is likely to deteriorate further.

Raising the retirement age could slow down this imbalance, but it would not reverse it owing to rising life expectancies, plus a large number of deferred members whose retirment age could end up “grandfathered”, while other yet active members of retirement age might rush to retire.

Chart B.

On average, active members—to say nothing of future joiners—are at earlier stages of their careers and hence contribute less per person than pensioners, who receive more per person. The imbalance in active versus pensioner numbers, and contributions versus receipts per person, magnifies funding risk prospectively.

To protect against this structural imbalance, fund assets must work ever harder (i.e., be relentlessly return-seeking) and take full advantage of their long-term investment horizon, all the while carefully managing current liquidity needs.

Fund officers and their advisors should consider building in protection against an array of unspecified adverse developments over coming decades by raising the fund’s shock absorbers, namely its capital buffer.

In their 2022 trienniel valuation, administering authorities might adopt as a funding objective raising to over 90% the probability of the fund having sufficient assets to meet future liabilities under a range of stochastic scenarios.

This implies that a de-risked, fully funded ratio of assets to projected liabilities might be closer to 150% than 100%.

Building up capital buffers

In terms of strategic asset allocation (“SAA”), talk of “de-risking” suggests taking some of the money off the proverbial table and accepting lower returns.

Instead, SAA deliberations should focus on how to “sweat the assets” efficiently by tapping into a diversified set of return sources, each capable of delivering an acceptable compounded return, and which in combination can offer natural internal offsetting properties.

Such an approach can help to create a capital buffer to insulate against future adversity. This approach is at odds with many LGPS funds that focus on generating current cash flow to meet growing projected net outflows—reflecting the membership imbalance—rather than compounding capital values.

In short, if fund assets do not work hard now to build sufficient capital buffers, looming risks like climate change and retrospective judicial decisions plus the growing structural imbalance of the LGPS membership could necessitate sharply rising contributions for active members in the future. This outcome could threaten the the sustainability and affordability of LGPS pensions for all. Target funding levels should rise far beyond 100% before anyone begins to feel comfortably funded.

Elizabeth M. Carey, CFA, works as an independent advisor and research analyst for local government pension schemes. She spent much of her previous career working in corporate finance and capital markets in New York and London, and subsequently worked as an in-house M&A banker for GE Capital in London. The views expressed in this article are her own.

Photo by Dan-Cristian Pădureț on Unsplash

—————

FREE monthly newsletters

Subscribe to Room151 Newsletters

Room151 Linkedin Community

Join here

Monthly Online Treasury Briefing

Sign up here with a .gov.uk email address

Room151 Webinars

Visit the Room151 channel