Donald Trump’s arrival in the White House begs big questions for the global economy. Erik Britton explores the implications for investors if the US decouples from the rest of the developed world.

It’s awkward when couples break up, especially when one partner was simply “not that into” the relationship. The other partner can react in two ways: philosophical resignation or angry spite.

Subscribe to our LGPS Quarterly Briefing and be first to receive more content like this.

Donald Trump (and, by extension, the US electoral college) is simply not that into the US’s trading relationship with the rest of us. We’ve just been dumped. How will we react?

Most likely, we will behave like adults, shrug wearily and move on.

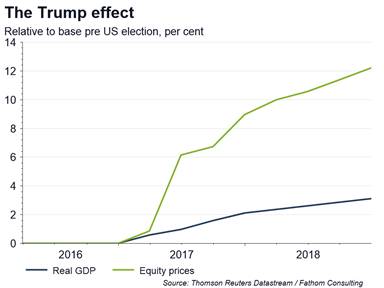

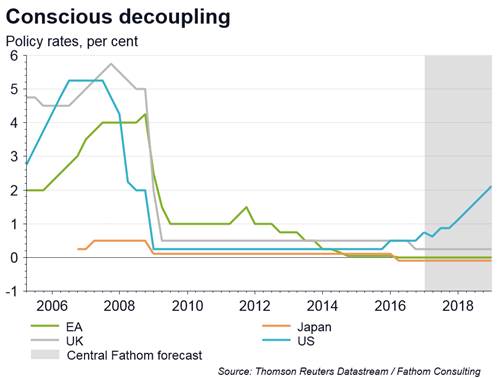

In that case, Donald Trump could go down in history as a highly successful, two-term president, responsible for igniting a boom in the US economy, a bull-run in US equity markets, and a decisive move away from zero interest rates. The US will decouple from the rest of the developed world, in terms of its growth and interest-rate environment, and in equity markets too.

How galling for the rest of us! You’ve just dumped someone, and then you start posting messages on Facebook (or, more likely, tweeting) about how great your holiday in Hawaii is, how you feel so relaxed now you’ve taken up yoga, how you’ve lost twenty pounds, and look at your new sports car…

The president elect has promised huge tax cuts, especially for corporations, alongside big increases in government spending: a fiscal “splurge”. Risky, given the current cyclical position (close to full employment) and the current debt position (net government debt around 100% of GDP, with substantial private debt on top of that). But the US is the world’s reserve currency, with no serious challenger for that position for the next twenty years at least. It can splurge all it likes, without any threat to the government’s future funding.

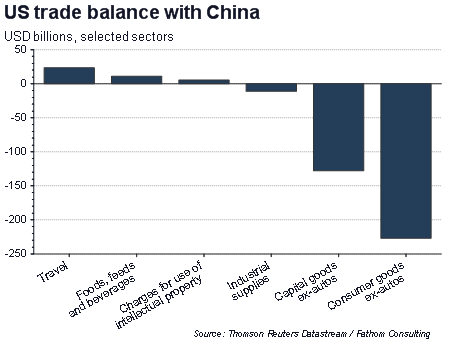

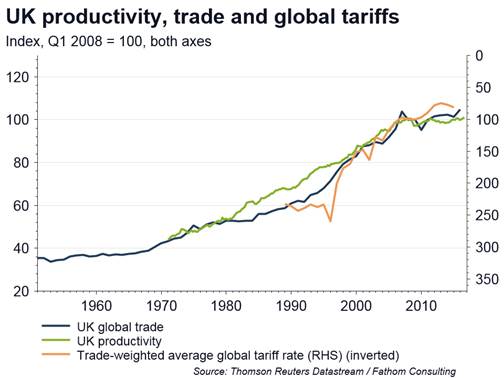

He has also promised to withdraw from those multilateral trade deals which he regards as bad, and impose import tariffs on those trading partners he regards as the worst offenders in artificially manipulating their bilateral terms of trade with the US, naming China and Mexico among those. If he follows through on that promise, it will imply: higher prices and wages for US consumers and post-tax profits for US producers; and a fiscal transfer to the US from the countries on whom the tariffs are levied.

If that’s the end of the story, the US economy will boom, US firms will enjoy higher profits, especially after tax, and real wages in the US will rise. Inflation will follow suit, and yields will return to “old-normal” levels. Capital will flood back into the US given the high yields available there, and the safety that dollar-denominated assets still represent.

This will be judged a triumph: a mixture of Reagan and FDR, bringing back the all-important “feel-good factor”. President Trump’s popularity will soar. The fiscal position will blow out, mitigated only partly by the fiscal transfer from abroad and the increase in the tax base at home. But that’s tomorrow’s problem.

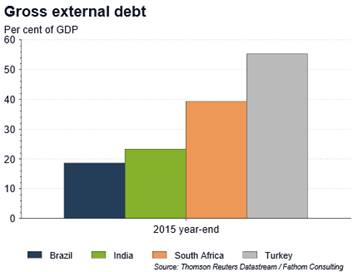

There will be losers, but most of them will be outside the US. China and Mexico, clearly, would number among them — and not just because of the tariffs. Commodity prices would rise on the back of a resurgent US, hurting commodity consumers the world over. Beyond those two countries, other emerging markets would suffer from the flight of capital back to the US — in the firing line would be those most reliant on capital inflows: those borrowing the most in global capital markets, especially where that borrowing is in dollars. But other emerging markets might benefit, especially those who compete with China and Mexico in global markets.

Elsewhere, other developed economies would benefit: first, from weaker currencies against the dollar; second from the “beta” in their equity markets relative to the US; and finally from the “coat-tails” effect of stronger demand growth in the US as an export market. That would probably add a few tenths to the growth rates achieved in the EU, Japan and other developed economies — from a low base. And interest rates would rise a little, particularly towards the longer end of the yield curve. But the spread between US rates and comparable rates in other developed economies would widen at all maturities: the US would decouple from the rest of the developed world.

The outlook for the UK would improve slightly, but not by enough to offset the dampening impact of Brexit on growth. Investment will slow, damaged by the uncertainty that Brexit creates, until the trade negotiations have been concluded. And the medium-term prospects for the UK were already bleak, with trend growth of around 1% to 1.5%, thanks to its unprecedentedly weak productivity performance. The UK will probably outperform the euro area and Japan, and the yield curve in the UK will rise by more than in the EA or Japan, but by a lot less than in the US.

We’ll still have the same old car, we’ll still be overweight, honouring our gym membership more in the breach than the observance, and relishing the prospect of a wet weekend in Skegness in the summer.

What if we take the other route, the vengeful, spiteful reaction? Tempting, isn’t it? We can hurt the US, certainly. But we would hurt ourselves even more in the process. This would see tit-for-tat trade restrictions spreading around the world, the election of the Five-Star movement in Italy and Marine Le Pen in France, a strong showing by AfD in Germany, a hard Brexit, a re-emergence of the euro crisis, a global banking crisis, a belligerent geo-political stance by China, aggressive behaviour by Putin in Europe, collapsing global commodity prices, instability in the Middle East, and so on.

That route leads to a re-run of the 1930s, with collapsing global trade, depression, deflation and debt default. We have no precedent for getting out of such a scenario, except via a world war – it’s the geo-political equivalent of a messy, acrimonious divorce. Nobody benefits. For now, this remains the less-likely outcome, but watch this space.

Erik Britton is managing director of Fathom Consulting.