Recent events have cast doubt over the future of shared services for local authorities. Graham Liddell argues they can still provide valuable benefits — if managed well.

It’s less than a year ago since the Tri-Borough collapsed and the Northamptonshire Best Value Inspection Report had some harsh words to say about the role of LGSS. Is this the beginning of the end of the shared service?

Of course it isn’t. Many shared services are well established and delivering improved service levels, economies of scale and greater resilience for their customers. So, what do you need to do to create a successful shared service?

Based on my personal experience and very unscientific analysis, I think there are three preconditions for success:

- Being crystal clear as to why you are entering into a shared service

- Building trust

- Providing clear leadership and creating capacity*

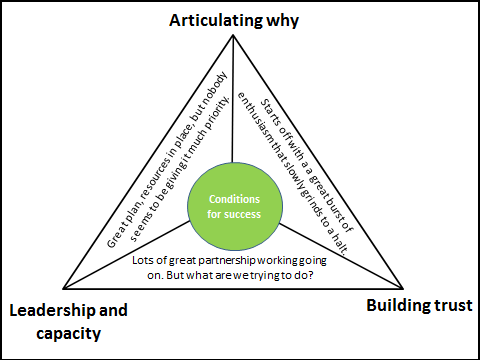

* I know that providing clear leadership and creating capacity are really two conditions, but I spent quite a lot of time coming up with this nice triangle diagram (see below) which shows what happens when you don’t pay enough attention to one of a set of three. So please bear with me and read on: it will all make sense in the end.

‘Three’ preconditions for shared service success

Condition 1: Articulating why

It’s a pretty fundamental question: Why do you want to create a shared service in the first place?

My shared service journey started as head of internal audit at Brighton & Hove. And for me, it was clear that by working in partnership with other local authorities, my authority would benefit because our staff would be able to deliver more effective audits.

We would keep our understanding of the culture and control environment of Brighton & Hove and develop further our knowledge, experience and skills by working with, and at, our partners. Understanding the why enabled us to articulate:

- Our purpose (focussed very clearly on the needs of the local authority).

- What made the shared service option better than the alternatives (in this case outsourcing or going it alone).

Articulating “why” might not appear that challenging, but I wouldn’t underestimate its importance. It’s about creating a common purpose that will guide everything from the overall shape of your service to your day to day decisions.

And in articulating why, there are two lessons I would like to share:

- It might be obvious, but if we are trying to develop a common purpose, the whole team needs to be able to contribute.

- If your “why” isn’t focussed around the needs of your customer, start again. If you are trying to create a shared service finance function, there isn’t much point investing all that time and energy to create one that doesn’t help its customers manage its finances.

Condition 2: Building trust

So, we have agreed a well-crafted and clearly articulated common purpose for our shared service. The trouble is that our key stakeholders (even those involved in developing the “why”) may not be as enthusiastic as we might expect.

- Members are typically suspicious about sharing control with other local authorities, particularly those with different political outlooks.

- The officer leadership team may feel that they will lose access to support staff they have come to rely upon.

- You can expect a whole range of anxieties from teams joining the shared service. Staff will inevitably be anxious about job security, but less obvious issues can have a big impact. Here are some snippets of conversations I have overheard:

—I don’t want to do things their way.

—They’re are a funny lot over there.

—I used to work with Bob, he’s a nice bloke but…

To these concerns we need to add the inevitability of things going wrong and (because we are working across more than one organisation) endless opportunities for misunderstanding and misinformation.

These are fundamentally issues about people and so our first line of defence is to work hard at developing relationships across the partners to build and maintain trust. This isn’t something that happens by osmosis. It’s something that leaders need to keep high on their agenda. There are a myriad of tools at your disposal, here are three.

- The best way of getting people to work together is (very simply) to get them to work together. There will be lots of opportunities (for both members and officers) to collaborate and learn from each other. Create as many of these as you can.

- Mind your language. Maintaining an awareness of the words we use is a great way to challenge attitudes. Dropping in a judicious “we” or “our” can help to build a sense of partnership. But possessive pronouns are dangerous. Frequent use of “them” or “us” in the wrong context can start to build barriers. Look out for inappropriate use of language and root it out. How about a swear jar?

- Experiment and fail fast. The shared service will need to experiment to find new ways of working. Success should always be celebrated but how we deal with failures is possibly more important. Failing fast means putting a stop to failing experiments as soon as it becomes clear that they are failing, learning the lessons and celebrating the courage of the innovation. Above all, avoid the long-lingering death of a doomed initiative followed by an attempt to find someone to blame.

Condition 3: Leadership and capacity

The first two preconditions are about setting direction and making sure that everybody up for the challenge of working in partnership.

But developing a shared service is a complex project where each partner has different starting positions and expects to have a say on any changes. The project can easily grind to a halt under the sheer weight of work and the intricacies of decision making.

Providing clear leadership and addressing capacity are critical to making sure that a complex project doesn’t become overwhelming. Here are some issues to look out for.

- Your teams will look to their head of service to provide clear and unambiguous leadership. The trouble is that each of the prospective partners will have their own heads of service, each of whom may be vying for this role in the shared service. This will need to be resolved sooner rather than later and will often require some difficult choices. Ultimately, though, there can only be one leader.

- One of the advantages of bringing together teams from different local authorities is that they can design a new way of working that takes the best from each. If we do this right, there is an opportunity to create capacity by developing processes that manage demand, are more streamlined, automated and focused on the needs of customers. The risk is, however, that by being over-cautious we compromise so much that we end up with each of the old processes layered on top of each other. The role of the leadership is to empower teams to make brave decisions that will create capacity.

- Don’t forget the that usual rules of managing projects apply:

—Get hold of a good project manager. They are worth their weight in gold.

—Don’t try to do everything at once. This is a long-term project and you will need to plan out what you are going to tackle and when.

—Make sure you have sufficient resources to release people to work on the shared service project without compromising the day job.

And finally…

So three preconditions: articulating why, building trust and leadership/capacity. If I had to choose which is the most important, it would be building trust. The shared service will be built by people taking leaps of faith to work for a common good. If they trust each other, they can work together on the other two.

Graham Liddell is head of finance (Technology and Process Improvement) for the Orbis Partnership.