Sponsored Article: A change in leadership often sparks intrigue from investors—particularly when the leader is the chair of the world’s most important central bank. Newly-minted Fed chair Jerome Powell arrives without a common credential on the CVs of modern central bankers: a Ph.D. Cause for concern? We think not.

On October 22, 1907, the annualized interest rate on overnight lending in the US banking system spiked to 100%.(1) A financial panic was underway and the richest American at the time, John Pierpont Morgan, stepped in and single-handedly provided much needed credit to Wall Street. His actions saved the day but also reminded policymakers that they could not rely on one man, who was often vacationing in Europe, to fix every financial panic.(2)

On October 22, 1907, the annualized interest rate on overnight lending in the US banking system spiked to 100%.(1) A financial panic was underway and the richest American at the time, John Pierpont Morgan, stepped in and single-handedly provided much needed credit to Wall Street. His actions saved the day but also reminded policymakers that they could not rely on one man, who was often vacationing in Europe, to fix every financial panic.(2)

Today, the US does not rely on billionaires to provide liquidity in times of stress. Instead, the central bank, the Federal Reserve, plays the role of “J.P.” Morgan.

Despite the change, the personalities at the helm of the world’s most important central bank still garner significant attention. With Jerome “Jay” Powell, a lawyer not an economist, taking the Fed’s reins in February 2018, we thought it prudent to discuss the “changing of the guard.”

Here, we dive into why we don’t worry about Powell’s lack of an economics Ph.D, why the real issue might be the change in the power dynamics at the Fed due to the many vacancies on its board, and how Fed chairs might not be as important as the economic cycles they find themselves in.

The Ph.D standard versus the Gold Standard

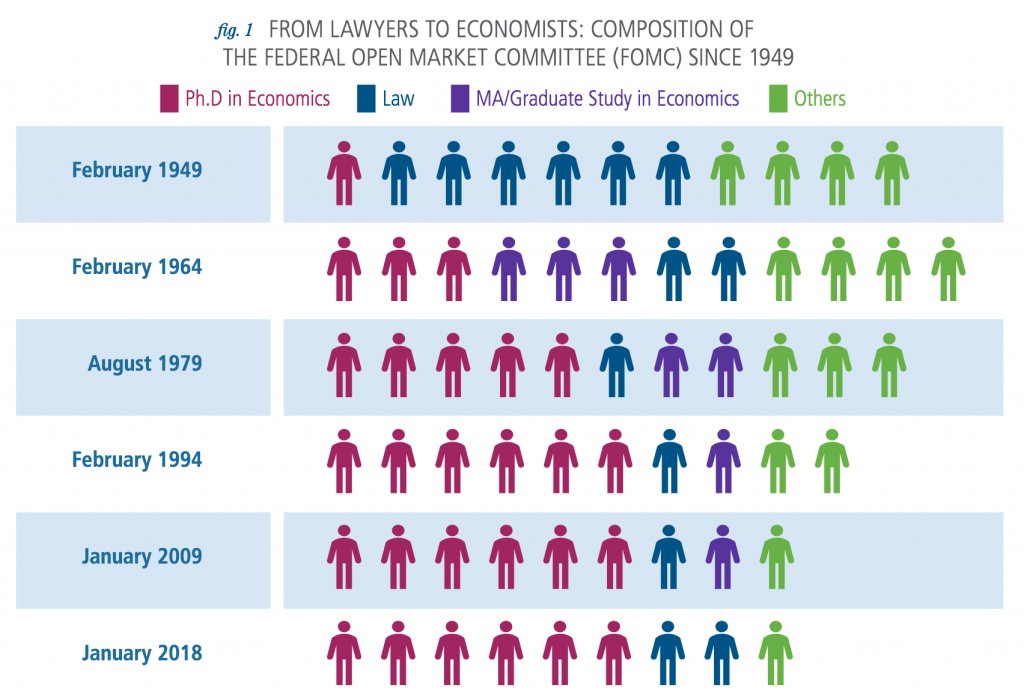

Fed watchers have obsessed over Powell’s lack of Ph.D credentials. More broadly, Ph.Ds dominate the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the rate setting committee of the Federal Reserve, to such an extent that Fed critic James Grant refers to our current monetary standard as the “Ph.D standard.”(3)

This was not always the case. While the last three Fed chairs held Ph.Ds, the two prior chairs did not. In 1979, Ph.Ds were in the minority on the FOMC (see Fig. 1). In fact, in 1949, the FOMC was comprised mostly of lawyers, just like Powell.

Some critics also point to Powell’s experience in the private sector (see Who is Jerome ‘Jay’ Powell?) as a detriment, recalling that the last Fed chair from the private sector, William Miller, had an abysmal track record.(4) The difference is that Miller had served as chief executive of industrial conglomerate Textron prior to appointment, while Powell, in addition to his private sector commitments, also served as a member of the board of governors for more than five years.

Further, Powell’s private sector experience in banking and public sector experience at the U.S. Treasury could serve as an asset to the Fed in times of trouble. In a way, Powell’s lack of a Ph.D might free him from the constraint of ivory tower thinking that earned his predecessors scorn. While his “doctor” colleagues were working on long papers with titles like Long-term commitments, dynamic optimization, and the business cycle, (5) before their tenure at the Fed, Powell oversaw (as a regulator) the near collapse of the Bank of New England, a regional commercial bank, and led the government’s efforts in the early 1990s bid-rigging scandal at Salomon Brothers, a major and seminal investment bank.

WHO IS JEROME ‘JAY’ POWELL?

Jerome H. Powell was born in Washington D.C., received his law degree from Georgetown University and spent most of his career inside the beltway. He also spent time at an investment bank and law firm in New York before heading back to DC in 1990 to work as assistant secretary for domestic finance at the US Treasury. During his time at Treasury, he oversaw (as a regulator) the near collapse of the Bank of New England and guided the government’s role during the Salomon Brothers bid-rigging scandal. He returned to private life at the influential investment firm, the Carlyle Group, where, coincidentally, Randal Quarles, a current Governor on the Fed Board, was also employed. At Carlyle, Powell made his fortune. He arrives at the Fed as one of the richest Fed chairs to hold the post (Marriner Eccles, of the famously ultra-wealthy Utah family probably keeps the top honor).

Finally, for those who worry that Powell might still need a healthy dose of academic thinking in order to lead a modern central bank in a complex global economy, it’s not like the Federal Reserve has a shortage of Ph.Ds.

In fact, the Fed is probably the largest single employer of economics Ph.Ds in the US, with more than 300 economists with the degree on its payroll. If two of the Big Four accounting firms can have chief executives who are not CPAs, then the Fed can have a chair who is not a Ph.D. An army of wonks awaits at his beck and call.

Vacant sears tilt the balance of power

While financial news outlets fixate on Powell, the focus should be on the many vacancies at the Board of Governors (see An Introduction to the Federal Reserve System). Unlike the US Supreme Court, where members often disagree publicly and cast individual votes, the Board of Governors tends to be unanimous in its decision making.

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM

The Federal Reserve System consists of the board of governors and the 12 Regional Federal Reserve Banks. All seven members of the Board of Governors, the president of the New York Fed, and four rotating presidents of the regional banks serve on the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the interest rate setting body of the Fed.

Behind the scenes, in meetings, other members can influence decisions, with the chair serving as a mediator, collecting the views into one consensus. It has been rare for members of the Board of Governors to oppose the chair’s vote when setting monetary policy at the FOMC. The last time a board member publicly dissented was in 2005.

Meanwhile, the regional Federal Reserve branch presidents tend to do most of the dissenting. In fact, presidents of the Federal Reserve’s 12 regional banks have dissented 70 times since 2005 (Neel Kashkari is currently doing what he can to increase this number).(6)

Four vacancies loom on the Fed Board of Governors as we go to print, the unfortunate status since Janet Yellen departed in February 2018. That means the empty seats outnumber the filled ones (4 to 3). Never, since the Fed began in 1913, have there been so many vacancies.

Vacancies also mean a lack of continuity from year-to-year, which makes the hand-off from 2017 to 2018 tricky for investors to gauge. Only Powell and Fed Governor Lael Brainard return from 2017’s voting roster.

The lack of continuity has little precedent: only twice before, in 1987 and 2007, did so few voters continue on from one year to the next.(7)

Additionally, the balance of power on the FOMC (which consists of the regional Federal Reserve Bank Presidents plus the Fed Board of Governors) has tilted to the regional presidents for the first time in the Fed’s history.

What this balance of power shift means for actual monetary policy remains an open, unanswered question. On the other hand, if these four vacancies are filled at some point during 2018, the Board of Governors and the FOMC will look very

different. While voting with Powell, these new members will assert a lot of influence on the direction of short-term rates.

Especially given Powell’s reputation as a consensus builder and not an authoritative policymaker (see Did You Know? Who is Jerome ‘Jay’ Powell? on previous page), these new faces could help shape monetary policy more than the chair alone. Until then, the balance of power on the FOMC tilts toward the regional Reserve Bank presidents.

Cycles matter more than chairs

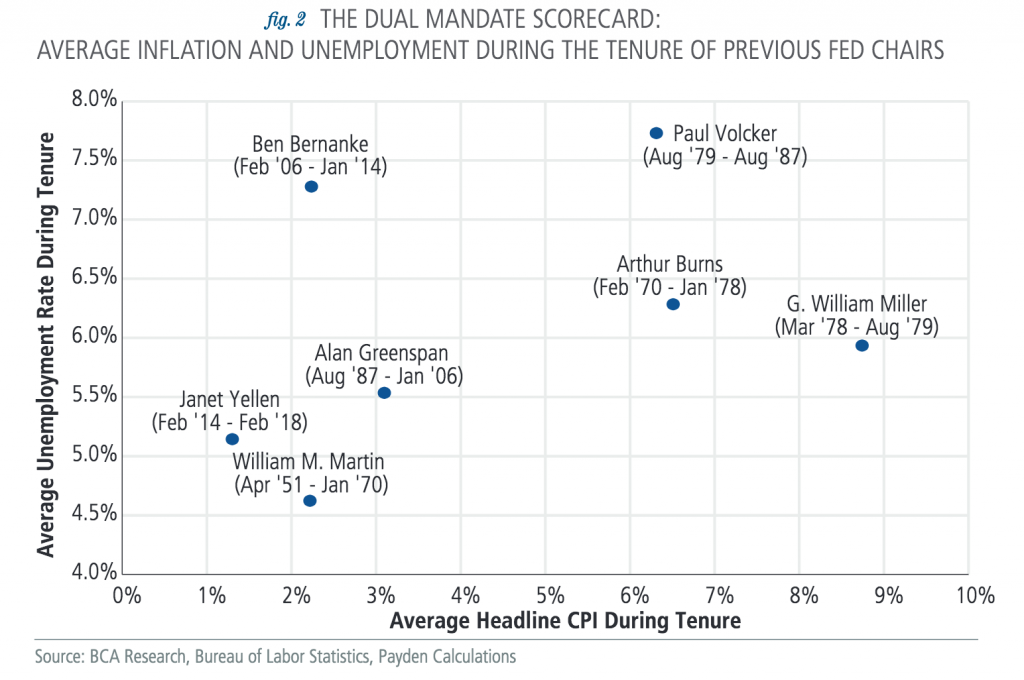

The US Congress sets the Fed’s dual mandate: keep inflation low and stable and target maximum employment. To see how past Fed chairs have done, we looked at the most well-known consumer inflation gauge, the Consumer Price Index (CPI), and the unemployment rate (see Figure 2 on previous page).

We find that economic cycles make the Fed chair the victim of circumstance rather than the hero

of the situation. After all, Fed chairs Martin and Burns oversaw the Fed with the Great Depression top of mind, and, as a result, were probably more focused on employment than low, stable inflation.(8)

No surprise then that inflation began creeping up during each of their tenures. Based on the high inflation and high unemployment observed during the tenure of Chair Volcker, one might be tempted to assign a failing grade (see

Fig. 2).

Chair Ben Bernanke took over the Fed on the cusp of the worst recession since the Great Depression—no

wonder unemployment skyrocketed on his watch. While Chairs Bernanke and Volcker deserve some credit for bringing down inflation (Volcker) and unemployment (Bernanke), they probably receive too much credit from the economic historians.

In the early 1980s, inflation was falling across the world after Volcker took over (did Volcker

do a tour of duty at the Bank of Canada, too?), and no matter who ran the Fed in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, interest rates were headed to the zero lower-bound.

In short, the macroeconomic environment drives the Fed chairs’ actions—but not vice versa. Most recently, former Fed Chair Janet Yellen held rates at the zero lower bound as the economy recovered from the 2008 financial crisis and only began to hike when the economy approached full employment.

As inflation edges toward the Fed’s 2% target, the Powell-run Fed will probably continue the pattern of a 0.25%

interest rate hike every quarter (one such move already occurred at the March FOMC meeting during the production of this article).

If, instead, inflation falls and unemployment starts to pick up—something we do not expect in the next year—then Powell would pivot and cut rates. If you wish to see how the economy will do and where interest rates will go, spend less time obsessing over every word Powell speaks and more time looking at macroeconomic data.

Pulling back the curtain on the Wizard of Oz

We believe the impact of a new Fed chair is not as important as many investors imagine. Even Alan Greenspan, notorious for his strong leadership coupled with abstruse public statements, faced debate within the monetary policy-making committee.(9)

Further, the Fed is a large and slow-moving bureaucracy that does not turn on the whim of one person. We see the vacancies on the Fed Board as a much more important variable to watch.

Jerome Powell’s succinct responses to members of the press and impeccable hair might not carry the weight of John Pierpont Morgan’s wealth, but Powell will be a successful consensus builder by “flatten(ing) the central bank’s traditional hierarchy and further liberaliz(ing) internal communication.”(10)

In the end, while it’s common to wish the new guard at the Fed the best in “steering” the US economy—it might be more apt to advise him to enjoy the ride.

Sources:

- Jon R. Moen and Ellis W. Tallman. The Panic of 1907. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Federal Reserve History.

- A Locked Door, A Secret Meeting And The Birth of The Fed, NPR Planet

- Money Podcast, December 29, 2013.Grant, Jim. Piece of my mind. Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, March 23, 2012.

- Miller’s appointment was supported by one of the most influential economists of the time, Milton Friedman. Go figure.

- The title of former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke’s 150-page thesis at MIT.

- Lacey, Tate. 2018: A Year Beginning with Turnover Questions at the FOMC. Cato Institute, Cato at Liberty

(blog), January 30, 2018. - ibid

- Should You Fear Looming Changes At The Federal Reserve? BCA Research, September 21, 2017.

- Peter Conti-Brown, The Power and Independence of the Federal Reserve (Princeton University Press, 2016).

- Condon, Christopher. Here’s How New Fed Chair Powell Is Changing Things Up. Bloomberg, February 16, 2018.

This article was first published in the latest edition of Payden&Rygel’s Point of View: Our Perspective on Issues Affecting Global Financial Markets.