Investors should be using the current lull to “health check” their portfolios, identify gaps and weaknesses, and put in place cheap mitigants. If disaster strikes, they are protected. If it does not, the cheapness of these hedges and the low cost of carry detracts only a little from performance.

“The quickest way to run out of time is to think you have enough of it.”

Stewart Stafford

2017 marks a decade since the financial crisis began. And ten years on, notwithstanding the tepid growth and societal challenges of recent years, markets are celebrating a decade of strong returns.

Since June 2007, the S&P 500 Index has almost doubled, once dividends are taken into account, and its total return is nearly 70% even after allowing for inflation. That represents an annualised return of 7% in nominal terms and 5.4% in real terms for those that bought at the highs of the last cycle and held through the pain to today.

Take it from the bottom of the cycle and returns are even starker. The annualised total return is 17.4%, thanks to a near quadrupling of the index from its lows in March 2009.

Look at any other indices around the world and we see the same pattern repeated in market after market. It is also repeated in asset class after asset class, with investors across almost everything (barring, perhaps, commodities in recent years) making stellar returns.

This is not another analysis of why. Rather, it is about what next and how best to plan.

The short answer to the first is no one knows. As the eminent economist J K Galbraith noted, the only point of economic forecasting was to make astrology look respectable.

There are times when one might beg to disagree with Galbraith. This is not one of them.

To call yields, FTSE levels, projected asset returns, not to mention Brexit, North Korea, central bank behaviour, quantitative tightening and their many many cousins, all with any certainty, requires omniscience or the reality agnostic bravado of a Trump.

In this maelstrom, investors have found themselves paralysed and rooted to today. Driven by their funding needs and liabilities, they are staying the course, maintaining their equity allocations and grasping returns where they can. The horizon has shrunk to the present and the strategy past that replaced with a blind hope that policymakers (and they) will somehow muddle through the uncertainty.

That is not an investment strategy.

Warnings

Just because we lack clear visibility does not mean that we cannot analyse. One may not be able to forecast the future, but we can identify the risks. And if we can identify the risks, we can also understand the opportunities that lie out there and plan.

To wit, the only certainty we have today is uncertainty.

Optimists will tell us that we are on the path to normalisation. Returns are there to be made, systemic risks have ebbed and even inflation is to be welcomed as a sign of returning to more mundane concerns than the impending collapse of another part of the financial ecosystem.

But there are enough warning signs as well. Notwithstanding the surfeit of political uncertainty, total GDP per capita growth over the last dozen years is lagging the Great Depression and its aftermath. Assets are expensive, central banks are too dominant and the yield-seeking hounds born of behavioural bias seem to be forming ever larger packs.

Critically, the metrics of market volatility embody this dichotomy, plumbing new lows.

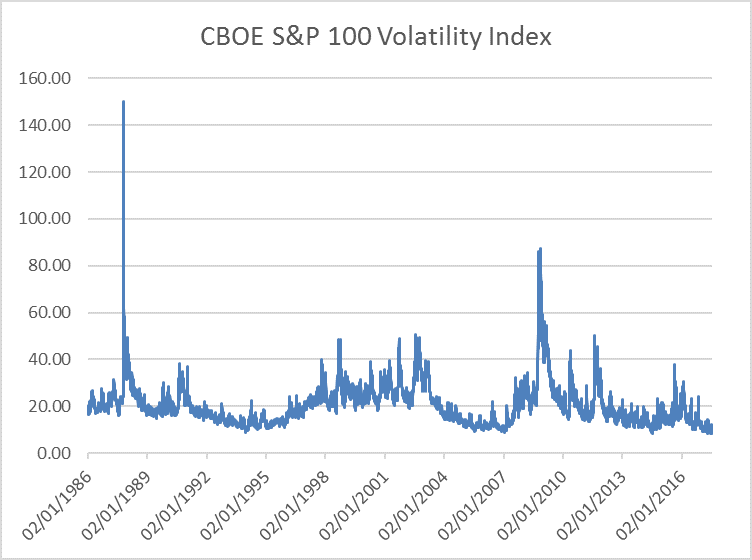

For most of this year, the Volatility Index has flirted with the boundary between single and double digits and has reached historical lows.

The lack of volatility reflects the emphasis on faith. It is also the most terrifying of all the pieces of evidence in support of a renewed normal.

Financial markets are not static entities. They are collective nouns for the actions born of the hope, greed, and fear of countless human participants. What they portray is emotion as much as any underlying economic reality and the volatility that we typically observe is driven by the competition between these emotions. Different worldviews vie for dominance, coalescing into temporary paradigms – transient accepted wisdoms – that ebb and flow over time, euphemistically creating the peaks and troughs of volatility we observe.

From this perspective, the (near) absence of volatility is not a boon. It is a reflection of the fact that there are no competing world-views. What we are seeing is clear signs of a herd mentality that has developed over the last decade.

That is a sign of fragility, not strength.

Doing nothing, or sitting out in cash on the sidelines is not an option, especially when liabilities are part of the equation. It also does not pay to be a bear these days. The disconnect between a world rife with uncertainty and racked by populist tension, and the euphoria of markets, as noted above, has created a bear trap for many.

Health check

But the low levels of volatility also represent an opportunity and a way forward.

They tell us that as we seek new opportunities and maintain current exposures, we should also begin to take some of the risk off the table. The lows and the sustained period spent around them are below the depths observed in late 2006 and early 2007 and, going further back, below those seen in the 1990s.

Those were the best and cheapest occasions to buy hedges and to insulate portfolios against unknown future risks. We do not know what trouble may strike, and if history is any guide, the next crisis will creep up unawares on most of us. But we do know that volatility will spike and that hedges, especially after the event, are expensive and largely useless. Brexit, for example, regardless of the path taken, will lead to volatility in the pound, interest rates and in inflation expectations and so on.

Investors should be using the current lull to “health check” their portfolios, identify gaps and weaknesses, and put in place cheap mitigants. If disaster strikes, they are protected. If it does not, the cheapness of these hedges and the low cost of carry detracts only a little from performance. That is the prudent thing to do in today’s environment, especially if investors want to safeguard the largesse of recent years.

It may be inflation. It may be central banks coming off the runway. It may be global debt – now at $105 trillion globally and some 50% above the levels of 2007. It may be populism.

These are enough canaries in the coalmine. Investors have derived a simple correlation in the last decade between monetary accommodativeness and rising asset prices, even in the face of future uncertainty. But there is no mathematical or economic relationship between the two, merely a psychological link based on perception and faith.

They should not confuse this with permanence.

As Ernest Hemingway noted in the 1920s, financial distress happens in two ways – gradually and then suddenly.

It behoves us to prepare for both.

Dr Bob Swarup is Principal at Camdor Global Advisors,

a macroeconomic, investment and risk advisory firm

focused on helping local authorities innovate to meet

today’s unique challenges.

He may be contacted at swarup@camdorglobal.com.